The Sisterhood of Mickalene Thomas: Create the Right Context, Then Focus and Celebrate

Mama Bush (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher

I recently enjoyed an exhibition of work by the African American artist Mickalene Thomas. (‘All About Love’ is at the Hayward Gallery, London until 5 May.)

‘With painting you can manipulate time, shaping how it’s perceived. It’s about exploring fantasy, illusion and the creation of desire.’

Mickalene Thomas

Thomas creates paintings, photographs, collages and installations that celebrate her family, friends and lovers. Her portraits are big, bold, colourful and confident. Conveying a very human presence with intimacy and intensity, they stop us in our tracks, hold us in their gaze.

‘To see yourself, and for others to see you, is a form of validation. I’m interested in that very mysterious and mystical way we relate to each other in the world.’

Born in 1971, in Camden, New Jersey, Thomas was raised by her mother, a former fashion model, who enrolled her in after-school art lessons at the Newark Museum.

‘It all began as a young child, when I recognised beauty and desire by the way the world responded to my mother’s beauty. My understanding of the complexity of desire began with how I perceived myself in relation to my mother. I became mindful of a desire to be the woman that she hoped I would be.’

As a teenager, Thomas moved to Portland, Oregon, and she subsequently studied at the Pratt Institute and Yale School of Art. She developed a particular interest in creating large-scale depictions of Black women.

‘I grew up with a lot of brothers, and I don’t have any sisters, so for me it’s really important to develop my sisterhood. It’s something I’ve always coveted.’

Painting in oil, acrylic and enamel, sometimes employing collaged black and white photos to add a touch of realism, Thomas inlays her work with multi-coloured rhinestones. Her subjects, dressed in vibrant, glamorous clothes and located in bright domestic contexts, are in repose, relaxed, at leisure. They regard us directly, with assured stares, seeming both self-possessed and vulnerable.

‘The love we make in community stays with us wherever we go.’

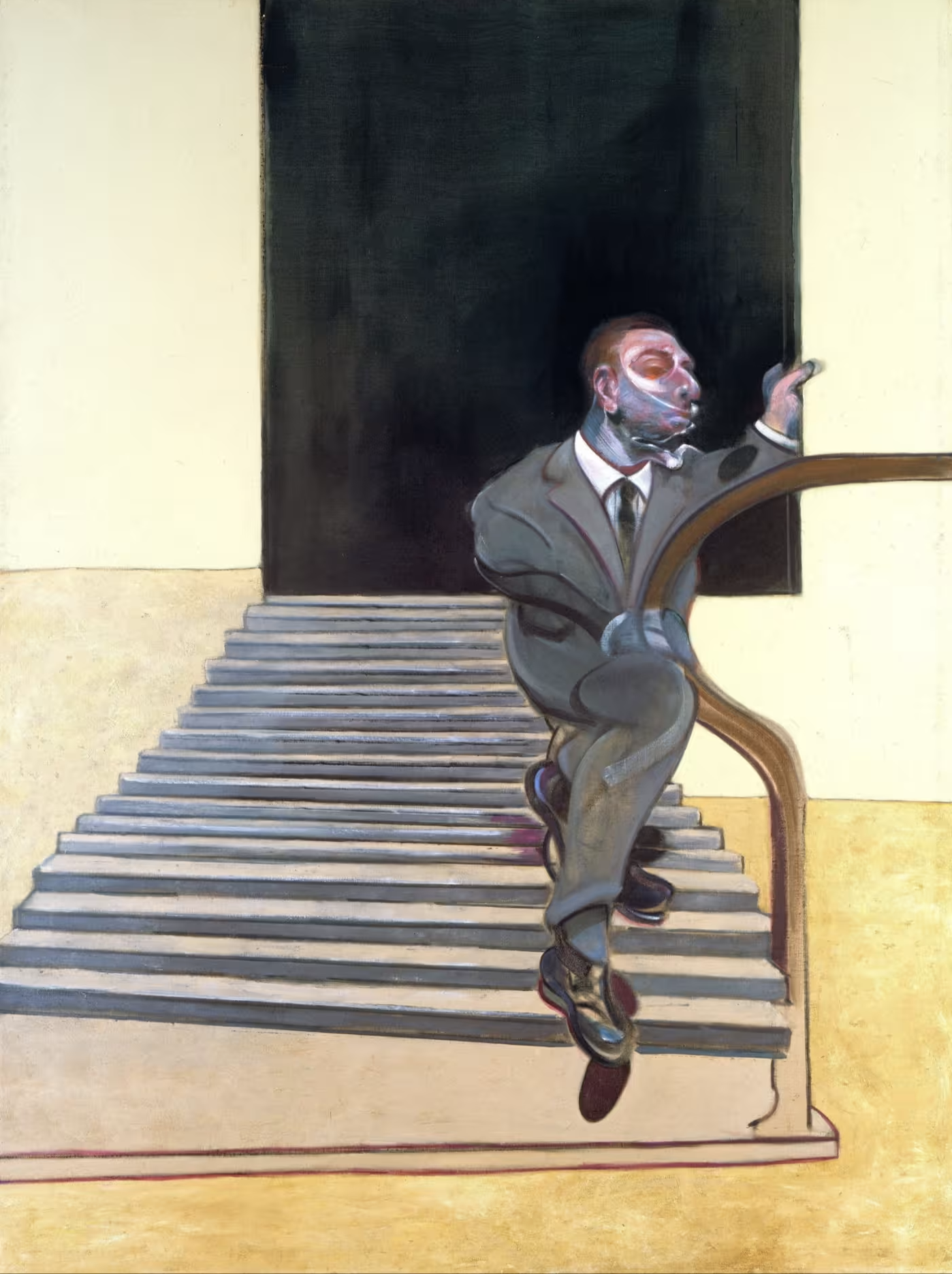

Often the poses and compositions echo the works of historical European painters - Ingres, Courbet, Manet, Monet – as Thomas seeks to reclaim art from its traditional white male perspective.

‘My work is rooted in self-discovery, celebration, joy, sensuality, and a need to see positive images of Black women in the world.’

Mickalene Thomas, Afro Goddess Looking Forward, 2015,

Rhinestones, acrylic, and oil on wood panel, 60 x 96 in (152.4 x 243.8 cm)

I was impressed by Thomas’ process.

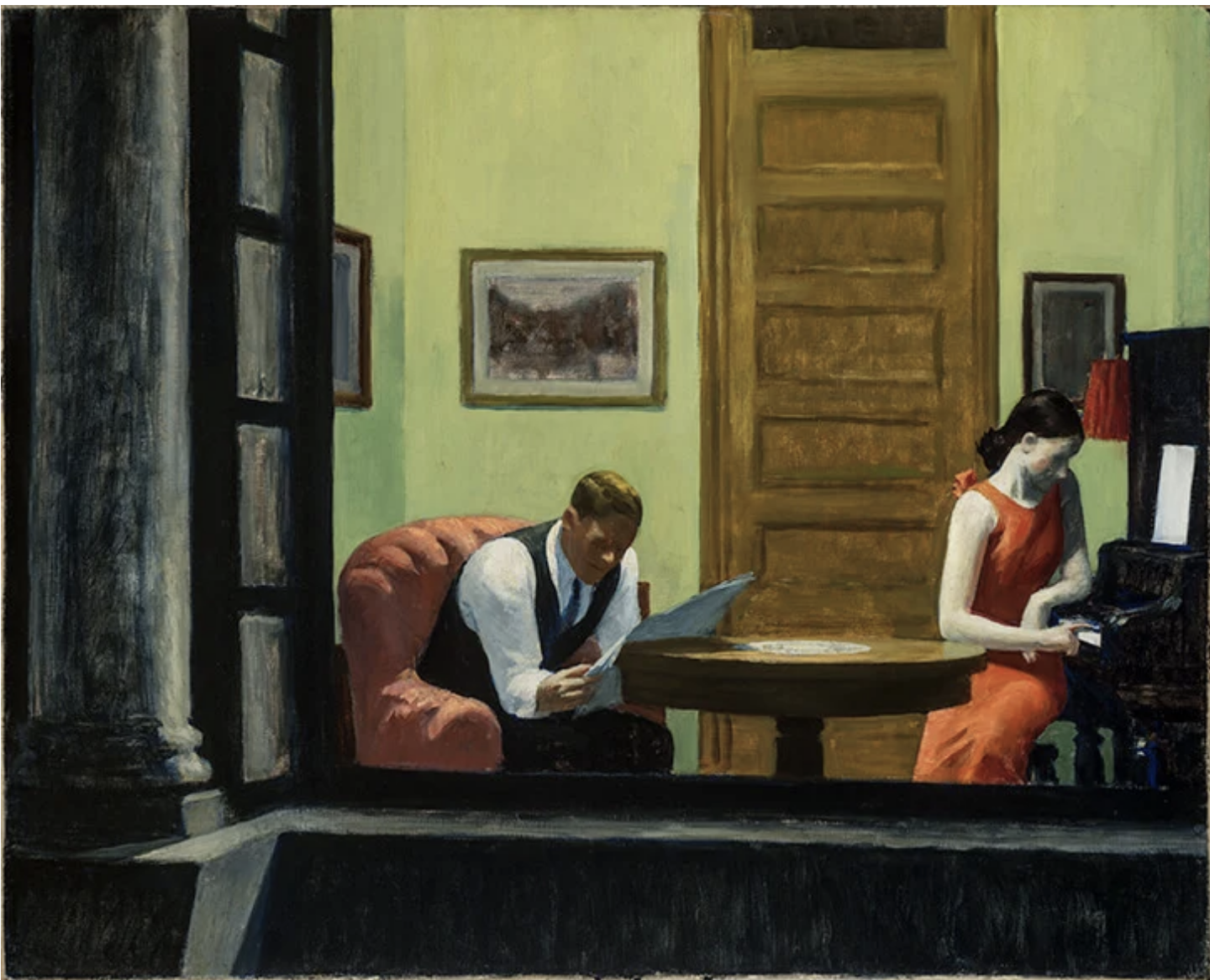

She first photographs her subjects in bespoke sets built in her Brooklyn studio. These interiors, draped with vividly patterned textiles, suggest warmth, security, the comfort of home.

‘I created domestic settings primarily for fellow Black women – my muses – to spend time and have new experiences in familiar surroundings, perhaps resembling their mother’s or grandmother’s living rooms.’

At the exhibition you can see a couple of Thomas’ living room installations, recalled from her own childhood: mirror walls, thick carpet, Tiffany lamp and pot plants; Donna Summer and Diana Ross LPs leaning against the music centre. She seems to be suggesting that our identity is shaped by the spaces we inhabit, the clothes we wear, the music we listen to.

Having put her sitters at their ease, Thomas then finds deeply personal connections with them. She focuses on who they truly are, celebrates them, elevates them.

‘Beauty has always been an element of discussion for Black women, whether or not we’re the ones having the conversation.’

In the world of commercial communication, we may recognise this approach: settle on the right environment; create an appropriate context; locate the brand in its own world. Then focus on, and amplify, its truth.

‘I define my work as a feminist act and a political act because I’m Black and a woman. You don’t necessarily have to claim that, but the act of making art itself is a political and feminist act when you’re a woman.’

There’s much to see at the exhibition beyond Thomas’ portraiture. I was particularly taken with a video piece inspired by Eartha Kitt’s 1953 song, ‘Angelitos Negros.’ The artist reimagines original footage of Kitt singing, combining it with images of herself. The lyrics ask why religious painters of the past filled the heavens exclusively with white figures.

It’s an absence Thomas seeks to address. She paints her own Black angels.

'Painters painting saints in church,

How do you know that God is white?

Painter, if you paint with love,

Paint me some Black angels now.

For good Blacks in Heaven,

Painter, show us that you care.

Paint me some Black angels now.

Paint me some Black angels now.’

Eartha Kitt, 'Angelitos Negros’ (Translation) (M Maciste, A Blanco)

No. 507