The Mediocre Pioneer: You Don’t Need to Be First, But You Do Need To Be Fast

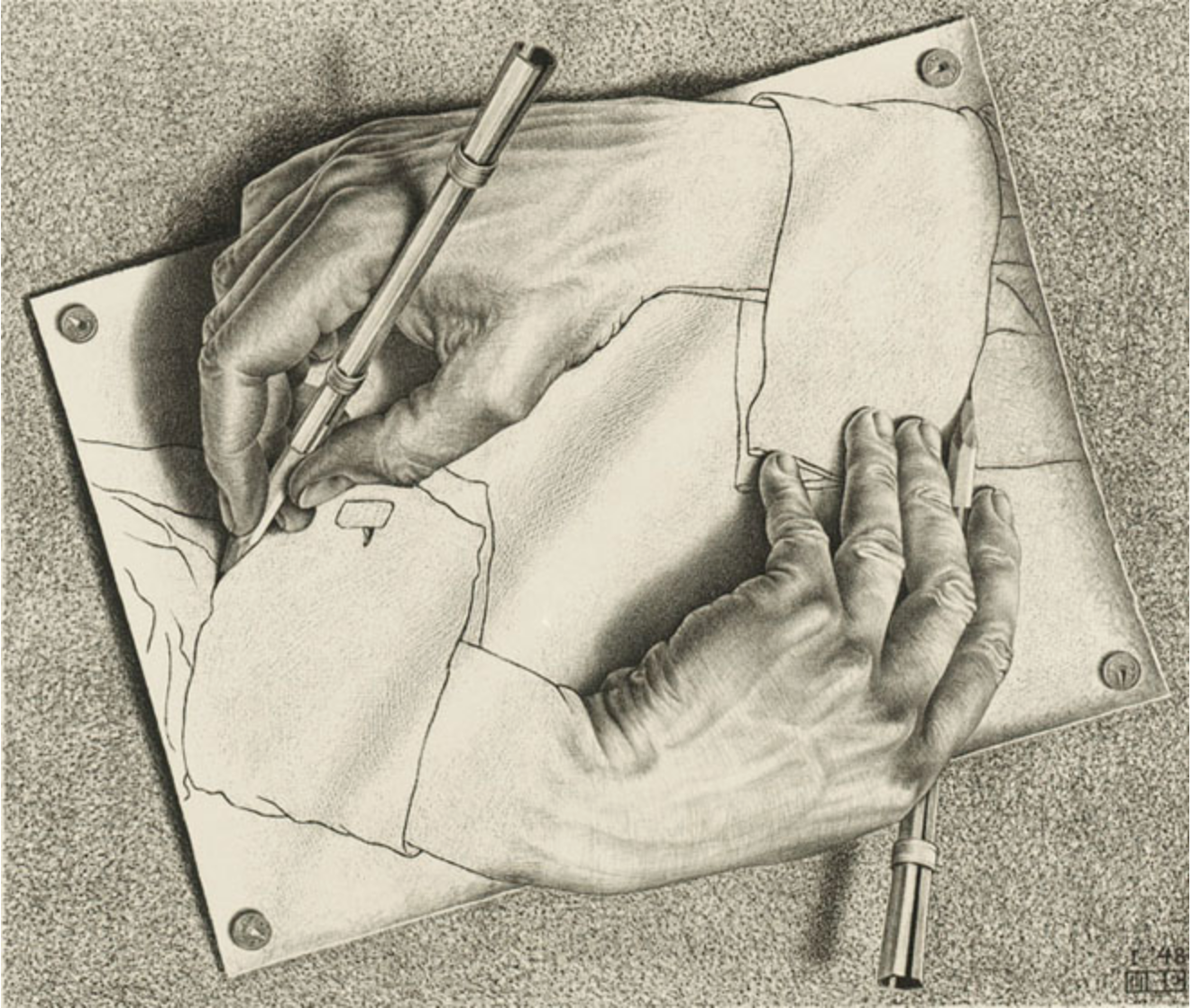

Still from Lights of New York

‘This is a story of Main Street and Broadway – a story that might have been torn out of last night’s newspaper.’

Opening titles, 'Lights of New York'

Warner Brothers’ 1927 movie 'The Jazz Singer' is celebrated as the first feature-length film with sound. It presents six songs performed by Al Jolson and contains two minutes' worth of synchronized talking. Famously Jolson’s first spoken words are:

'Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain't heard nothin’ yet.'

However, the rest of the dialogue in 'The Jazz Singer' is conveyed through the caption cards that were standard in the silent era.

The first truly all-talking feature film is a lesser known work.

'Lights of New York,' a crime drama directed by Bryan Foy was released by Warner Brothers the year after ‘The Jazz Singer.’ It was originally intended as a low budget, two-reel short. Foy had no experience with features. But while the studio heads were out of the country for the European premiere of ‘The Jazz Singer’, he filled out the plot and shot four reels more than promised. His costs went from the allocated $12,000 to $23,000.

Warners had been planning to make the first all-talkie a prestige picture and they ordered Foy to cut the film back to its originally agreed length. But the money had been spent and, after a couple of positive private screenings, the studio determined to give 'Lights of New York' a nationwide release in its full 57-minute duration.

‘This 9 o’clock town is getting on my nerves.’

A small-town innocent is duped by bootleggers into borrowing money and setting up a barbershop in New York. He soon realises that his business is merely a front for a speakeasy - The Night Hawk, a club ‘where anything can happen and usually does.’ To make matters worse, our hero’s sweetheart, who works as a performer at the club, has caught the eye of its crooked boss. A consignment of liquor is stolen, a cop is murdered, a lover is jilted, the good guy is framed. There is a gripping climax.

‘Lights of New York’ is an entertaining enough yarn and an interesting piece of social history. It immerses us in Prohibition era America and is rich with authentic city slang.

‘You know I’m not a squealer, don’t you? I’ve always been on the up-and-up.’

‘This guys got a streak of yellow a yard wide.’

‘I want you guys to make him disappear. Take him for a ride.’

Despite these charms, the new sound technology imposed considerable constraints on the production. Actors cluster round a microphone strategically placed in the telephone on a desk. They huddle near a lampshade, squat around a hat stand, congregate next to a vase of flowers. It’s all a little awkward.

Most contemporary critics were unimpressed. While The New York Times recognised the film's significance as ‘the alpha of what may develop as the new language of the screen,’ other reviewers were scathing.

‘In a year from now everyone concerned will run for the river before looking at it again.’

Variety

‘It would have been better silent, and much better unseen.’

The New Yorker

And yet the brickbats did not deter audiences, who were simply thrilled by the novelty of sound. The movie grossed $1.2 million at the box-office and by the end of 1929 Hollywood was exclusively producing sound films. The silent era was over.

What are we to learn from ‘Lights of New York’? It’s not a great movie and it’s rarely watched nowadays. As US golfer Walter Hagen once famously observed:

‘No one remembers who came in second.’

Nonetheless, the film plays an important part in the history of cinema and it was incredibly profitable in its day.

Foy demonstrated that in times of change you’ve got to sidestep bureaucracy, recognise that there’s only a brief window of opportunity and seize the day. When an industry is reinventing itself, actions speak louder than words. You don’t need to be first, but you do need to be fast.

Sometimes timing trumps quality. And sometimes it’s smart to be a mediocre pioneer.

‘You want me to hide all my feelings.

And you want me to stop loving you.

But I’m a woman filled with pride.

I’ve been hurt deep inside.

I find it’s easier to say than do.’

Bettye Lavette, ‘Easier to Say (Than Do)’ (BB Cunningham and G McEwen)

No. 398