‘Seeing More Deeply’: Hilma af Klint, the Abstract Pioneer

Staggering’: The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907. Photograph: Albin Dahlström/Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

‘Every time I succeed in finishing one of my sketches, my understanding of humanity, animals, plants, minerals, or the entire creation, becomes clearer. I feel freed and raised up above my limited consciousness.’

Hilma af Klint

I recently watched a fine documentary by Halina Dyrschka about the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (‘Beyond the Visible’, 2019).

Af Klint produced a prodigious amount of thrilling work in the early 20th century. She pioneered abstract art – painting her first abstract piece in 1906, five years before Kandinsky. She experimented with new creative techniques twenty years before the Surrealists. And, as the film demonstrates, her work foreshadowed that of Mondrian, Klee, Warhol, Twombly and Albers.

However, af Klint was intensely private and not inclined to self-promotion. She rarely exhibited her paintings, and she requested that, after her death, her work should be hidden away for twenty years. Art historians, until recently, chose to ignore her, because she was inspired by her spiritualist beliefs - and because she was a woman.

Artist Hilma af Klint in her studio at Hamngatan, Stockholm, circa 1895. Photograph: Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Let us consider what we can learn from this remarkable painter.

1. ‘Explore the Infinite Possibilities of Development’

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862, in Solna, Sweden. Her father was a naval officer and mathematician, and most of her childhood was spent in the cadet school at Karlberg castle. In the summers the family adjourned to an island in Lake Malaren, and it was here that she developed a fascination with nature.

In 1882 af Klint enrolled at the Royal Academy of Arts in Stockholm and, after graduating with honours, she was awarded a studio in the city’s artist quarter. Dressed in black, with neat hair and cool blue eyes, she quietly worked away at her landscapes, botanical drawings and portraits, gaining recognition and financial independence. She was a shy, gentle person. But she had a fierce yearning to explore.

‘In this moment, I’m aware, living as I do in the world, that I am an atom in the universe, possessing infinite possibilities of development. And I want to explore these possibilities.’

2. Take Inspiration Wherever You Find It

Af Klint became interested in spiritualism and the occult, and her curiosity was enhanced when in 1880 her ten-year-old sister died.

‘What I needed was courage, and it was granted to me through the spiritual world, which bestowed rare and wonderful instruction.’

Af Klint’s fascination with the paranormal was not unusual at the time. Many intellectuals sought to reconcile a growing awareness of the plurality of religions with an acknowledgement of scientific progress.

‘Accept, accept, Hilma… Hilma, you were brought here to do this.’

In 1896, with four female artist friends, af Klint established The Five. The group held séances every week and recorded mystical thoughts and messages from spirits called The High Masters. They also experimented with free-flowing writing and drawing; with intuitive and spontaneous ways of creating art, opening themselves up to their unconscious selves.

Af Klint believed that a force was guiding her hand in the act of creation.

'The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.’

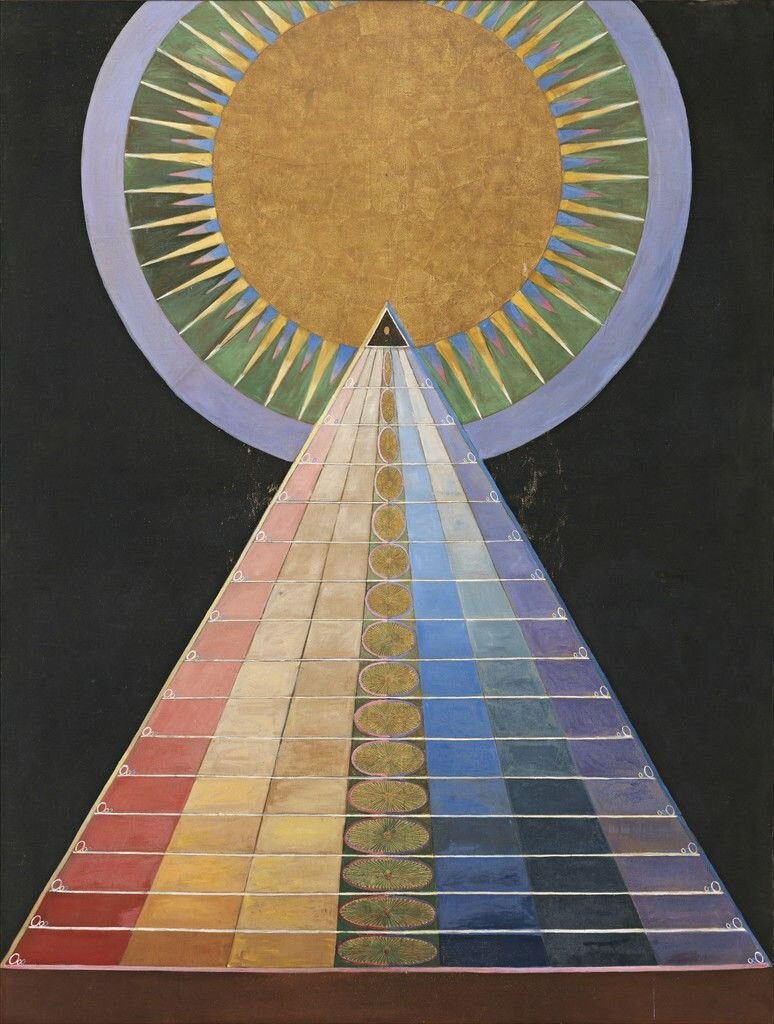

Hilma af Klint Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece (Grupp X, nr 1, Altarbild), from Altarpieces (Altarbilder), 1915. Guggenheim Museum

3. ‘See Beyond Form’

As scientific interest at the time focused on the world beyond the visible – sub-atomic particles, x-rays, gamma rays and radio waves - so too af Klint wanted to see beyond her already acute understanding of physical form.

‘Those granted the gift of seeing more deeply can see beyond form, and concentrate on the wondrous aspect hiding behind every form, which is called life.’

In 1906, at the age of 44, af Klint painted her first series of abstract paintings and, in a torrent of creativity, she went on to produce 193 pieces, some of which were extremely large - measuring over 2 metres by 3 metres.

Af Klint painted biomorphic and geometric forms; segmented circles and bisected spirals; shapes suggesting shells, butterfly wings, flowers and fans; cellular structures; beams and hoops, cones and curves; all rippling and pulsing, overlapping and intersecting. She used bold, soft colours: feminine blue and masculine yellow; pink and red for physical and spiritual love; golden orbs. There were symbols, letters and words; swans and doves; dualities expressing heaven and earth, good and evil.

Af Klint imagined installing the collected work, themed around the different phases of life from early childhood to old age, in a grand spiral spiritualist temple.

‘My mission, if it succeeds, is of great significance to humankind. For I am able to describe the path of the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.’

4. ‘Through Nature We Can Become Aware of Ourselves’

After Af Klint completed the Paintings for the Temple in 1915, she continued to explore abstraction and mystic themes, but without spiritual guidance. Her work became smaller, she experimented with watercolour and she produced more than 150 notebooks of thoughts and studies.

‘The more we discover the wonders of nature, the more we become aware of ourselves.’

In 1920 af Klint moved to Helsingborg, a coastal city in Southern Sweden and she committed to examining the wondrous truths in the natural world around her.

‘I shall start with the world’s flowers. Then with the same care I shall study whatever lives in the waters of the world. Then comes the gate into the blue ether with its many species of animals. And finally I shall enter the woods to study the damp mosses, all trees and animals living among the cool dark multitude of trees.’

Group IX/SUW, No. 17. The Swan, No. 17, by Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

5. ‘Achieve Stillness in Both Thought and Feeling’

Af Klint was a fiercely independent thinker, a vegetarian, a loner who didn’t need the affirmation of others. Having spent a lifetime contemplating existence, she seems to have attained peace.

‘Only for those prepared to leave their familiar life behind, will life emerge in a new gown of continually expanding beauty and perfection. But in order to attain such a state, it is necessary to achieve stillness in both thought and feeling.’

6. Don’t Hide Your Light, or Let Your Light Be Hidden

Though af Klint was wholeheartedly committed to spiritualism and her artistic path, she rarely had the confidence to show her work to her contemporaries, and she only exhibited a few of her abstract paintings at paranormal conferences. She was not actively engaged with the artistic movements of her time, and to the outside world she maintained the profile of a conventional landscape artist.

In 1908 af Klint had invited Rudolf Steiner, the founder of a spiritualist movement whom she greatly admired, to view her abstract paintings. Much to her dismay, he disapproved of them and of her claim to be a medium, and he advised her not to let anybody see the work. The setback prompted her to give up painting for four years and she concluded that the time was not right for her abstractions.

Af Klint wrote a will leaving all her art to her nephew and stipulating that it should only be made public twenty years after her death. Accordingly more than 1200 paintings and drawings, 100 texts and 26,000 pages of notes and sketches were carefully stored away.

The Ten Largest, №7., Adulthood, Group IV, 1907 Tempera on paper mounted on canvas 315 x 235 cm Hilma af Klint

Af Klint died in Djursholm, Sweden in 1944 following a traffic accident. She was nearly 82 years old.

Perhaps it was no surprise, given all this, that when in the 1940s and 1950s the Museum of Modern Art in New York set about defining the history of modern art, af Klint did not feature. Yet even when her archive was opened at the end of the 1960s, recognition came slowly. In 1970 her paintings were offered to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, but the donation was declined unseen, due to scepticism about her spiritualism. This seems particularly unfair, since many artists working in the same period, including Kandinsky, Mondrian and Malevitch, were also enthusiasts for the paranormal.

‘You must learn to ignore fear, for without the will to believe in yourself, nothing good will happen.’

Now, at long last, af Klint is being given the credit she deserves. In 2018-19 more than 600,000 visitors attended her first major solo exhibition in the United States: ‘Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future’ at the Guggenheim in New York. It was the most-visited show in the museum’s history.

Af Klint had finally found her grand spiral temple.

Hilma af Klint Exhibition @ Guggenheim. Photo: Radiofreemers

'All the modern things

Have always existed.

They've just been waiting

To come out

And multiply

And take over.

It's their turn now…'

Bjork, ‘The Modern Things’ (B Gudmundsdottir / G Massey)

No 324