A Big Order in a Crowded Bar: Creative Thinking in the Twilight Zone

Busy Bar by Norman Cornish

I had a big order: six pints of two bitters, a pint of lager, a Lucozade and a selection of different flavoured crisps. It was really crowded at the bar. People were elbowing their way past each other, waving and shouting for the publican’s attention.

I made my way up some rickety backstairs to a smaller, more secluded bar that I imagined few people would know about. Sadly, when I arrived, it too was rammed.

I was going to take ages to get served. My friends would be wondering where I’d got to. And it wouldn’t be too easy carrying that large order down those rickety stairs on a tray.

I was in a real quandary. What on earth was I to do?

And then I woke up.

'Yes: I am a dreamer. For a dreamer is one who can only find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he sees the dawn before the rest of the world.’

Oscar Wilde

I often forget my dreams, but this one stayed with me. I began pondering what it could mean.

It’s true. Bar presence is a critical life skill, and one in which I’m sorely lacking. Perhaps I have been wrestling with this shortcoming in my subconscious.

I’ve also read that dreams could be placeholders for other, deeper anxieties. Could my nightmare of the big order in a crowded bar indicate a more profound concern about my competitive competence, the struggle to achieve, the yearning to make a mark?

Then again, dreams are not just expressions of one’s inner cogitations. They can also be creative catalysts, sparks to original thought.

I read recently in The Times (December 14, 2021, 'Wake up your hidden creative powers’) about a study conducted at the Paris Brain Institute into hypnagogia, the transitional state of consciousness between waking and sleeping.

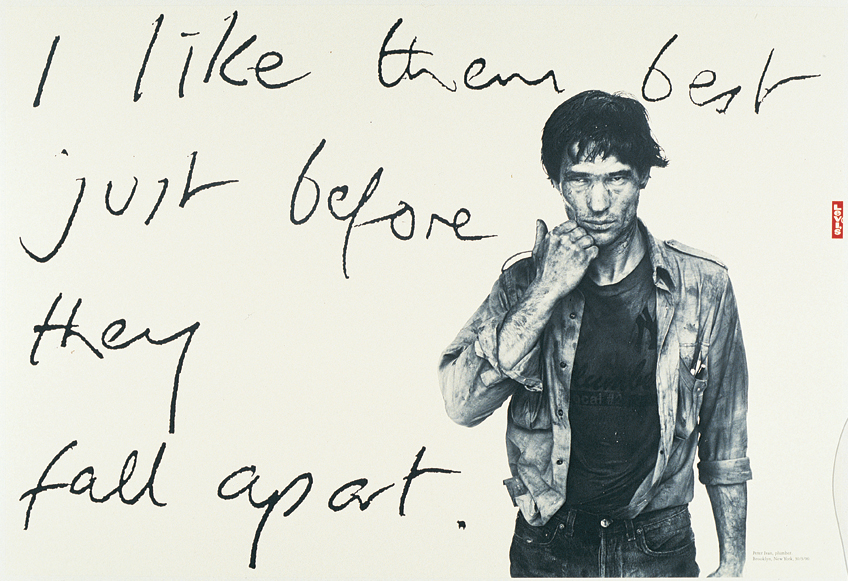

A team of neuroscientists and sleep doctors was keen to investigate a creative thinking technique used by inventors and artists. Practitioners would take a nap holding an object. (Thomas Edison used a metal ball. Salvador Dali clutched a key above a plate.) As they drifted off to sleep, they would drop the object and so wake themselves up at precisely the point before deep sleep. They believed this exercise, by accessing the ‘twilight zone’ between waking and sleeping, would inspire greater leaps of the imagination and more lateral problem solving.

Salvador Dalí demonstrates his creativity technique

Patrice Habans Getty Images

'Hold fast to dreams,

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird,

That cannot fly.'

Langston Hughes

The research recorded the brainwaves of more than a hundred people tackling a difficult maths puzzle over a long period of time. In the middle of the study participants were given a 20-minute break in which they relaxed with their eyes closed while holding a bottle. If they drifted off and dropped the bottle, they would be woken up.

The puzzle had embedded within it a 'hidden rule’ that would enable participants to get to the solution much more quickly. Of those who managed to stay awake the whole time 31 per cent found the shortcut, compared with only 14 per cent of those who fell into a deep sleep during the break.

However, there was another group - those who drifted into the non-rapid eye movement sleep stage 1, or N1. 83 per cent of this sample found the shortcut.

The scientists concluded that the N1 respondents performed so well in the test because this semi-lucid, liminal state enabled them to 'freely watch their minds wander, while maintaining their ability to identify creative sparks.'

'Our findings suggest that there is a creative sweet spot within the sleep onset period… We know that the twilight period is a moment in which memories are replayed and new associations are made. This could in turn explain why some people report having explicit breakthroughs during these short sleep episodes.'

I have tried the ‘twilight zone’ creative thinking technique at home. Sadly, each time I’ve woken up in a grumpy mood, with no dream recollection and a concern that I may have smashed a bottle on the living room carpet.

Nonetheless, I’m sure we should regard dream states as useful provocations to the more linear processes and patterns of everyday thought, as rich seams of ideas and insight.

'Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.'

Edgar Allan Poe

And so I’m prompted to reflect back on my nightmare of the big order in a crowded bar. Could I perhaps derive some creative inspiration from six pints of two bitters, a pint of lager, a Lucozade and a selection of different flavoured crisps?

Erm, I’m not sure. But at least it suggested this article.

'It was a cold day outside today,

I had nothing to do,

So I thought about you.

And then my friend said, "Lets go for a walk,"

Just to clear the air,

Well I thought about you.

The clock keeps ticking,

Cars keeps passing,

And the day goes by, slowly by.

I've nothing to do, but to think about you,

Think about you.’

The Scars, ‘All About You’ (D Child / P Stanley / A Carlsson / A Carlsson)

No. 355