Molly Drake: ‘I Remember Firelight and You Remember Smoke’

Molly Drake

Molly Drake was born into English middle-class privilege, endured the vicissitudes of war, raised two gifted children, and suffered terrible family trauma. She was also a remarkable poet and musician who did not publish any of her work during her lifetime.

For her, creativity was a private pursuit; a natural articulation of her thoughts and feelings; an expression of talent that didn’t need recognition or affirmation.

‘I sometimes think when it is time to die

I may perhaps have learnt the way to live.

I may have learnt to sift from out the grain

The chaff of littleness that blurs my eyes,

Small worries, little thoughts and little ways,

That creeping canker of insignificance

That eat away the very heart of life

And leaves behind the dull and flaccid shell.

I live hard, and oh, I hardly live

If living is become life’s only business.

And so I go stumbling and all perplexed,

Puffed on the dreary wind of little fears,

An eddied leaf jostled upon the tide

And seeing not the tide’s magnificence.’

Molly Drake, ‘Martha’ (Poem)

Molly was born in 1915 to military parents stationed in Rangoon. Educated in England, she returned to Burma, where she met and married Rodney Drake. With the outbreak of World War 2, Rodney enlisted and Molly made the gruelling trek on foot to Delhi with her sister Nancy. In comparative safety there, she formed a musical duet with Nancy, and worked as a co-host on All India Radio. Towards the end of the war, she was reunited with her husband, and gave birth to their two children, Gabrielle and Nick.

In 1952 the Drakes moved to England, to Tanworth-in-Arden, where Molly spent the rest of her life. As well as raising her children, she composed poems and songs, and played the piano for family and friends.

‘I never thought I was glamorous,

Nor dreamed I could inspire

Feelings that were amorous,

Red-hot flames of desire.

But now the door has opened on

A land of milk and honey.

It’s wonderful, it’s marvellous

But Lord! It’s terribly funny.’

Molly Drake, ‘Laugh of the Year’ (Song)

Molly was quiet, shy and somewhat reclusive, and her life was in many ways typical of a woman of her era and class. It was marked by conventional milestones; sustained by the usual hopes and disappointments; encumbered by the ordinary domestic duties. And yet it also saw terrible tragedy.

Gabrielle grew up to become an actor and Nick a musician. But Nick had poor mental health, and in 1974, aged 26, he was found dead due to an overdose of antidepressants.

Molly dealt with her grief in the old-fashioned way. She didn’t complain. She kept busy. She wrote, composed and played. She carried on.

‘But time is ever a vagabond,

Time was always a thief.

Time can steal away happiness,

But time can take away grief.

So I won’t try to remember,

For that way leads to regret.

No, I won’t try to remember

What I can never forget.’

Molly Drake, ‘Do You Ever Remember?’ (Song)

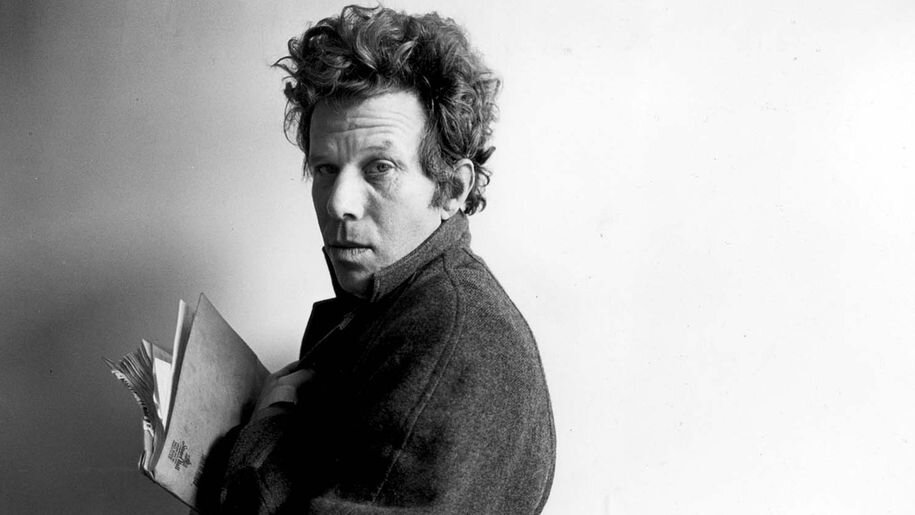

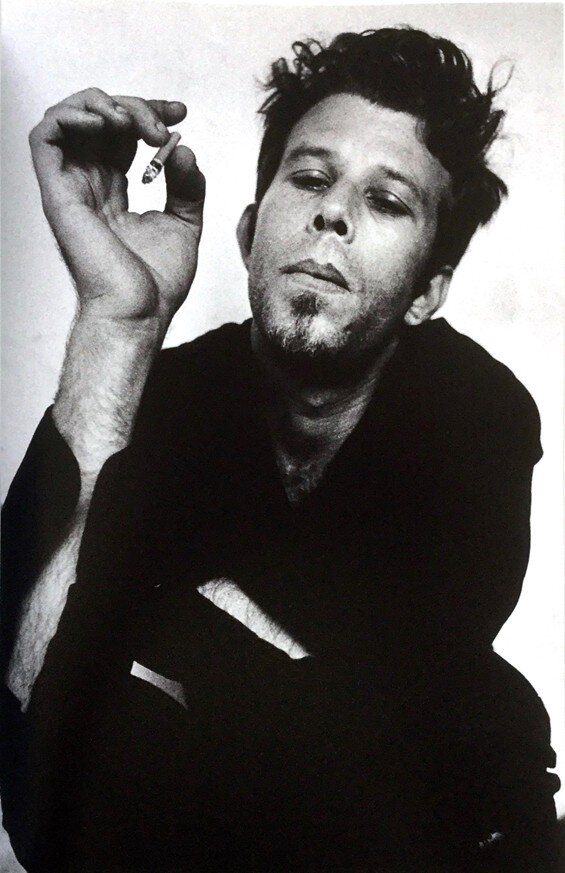

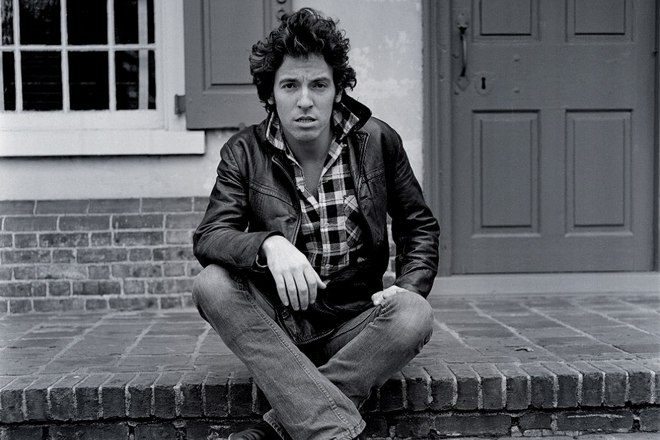

Molly Drake and Nick shopping

With Rodney’s help, in the 1950s Molly recorded some of her songs at home on a reel-to-reel tape machine. The recordings were later re-engineered by John Wood (who had worked closely with Nick) and finally issued in 2013.

Accompanying herself on the piano, Molly sings tunefully, mournfully, in a Home Counties accent. With precise phrasing and occasionally a wry smile, she tells of mercurial love and fleeting happiness; of consoling nights and sustaining dreams. She relates stories of birds and butterflies; wild winds and summer rains; of the pain of nostalgia and forced separation; of regretful recollections and the constraints of motherhood.

I was particularly struck by one composition, ‘I Remember,’ in which Molly recounts how a couple have completely different memories of the same events.

'We tramped the open moorland in the rainy April weather,

And came upon the little inn that we had found together.

The landlord gave us toast and tea and stopped to share a joke,

And I remember firelight,

I remember firelight,

I remember firelight,

And you remember smoke.

We ran about the meadow grass with all the harebells bending,

And shaking in the summer wind the Summer never ending.

We wandered to the little stream among the river flats,

And I remember willow trees,

I remember willow trees,

I remember willow trees,

And you remember gnats.’

Molly Drake, ‘I Remember' (Song)

At the conclusion of this recording, you can just make out Rodney’s quiet approval:

‘I should think that's really good.’

Memory is an elusive space, sometimes crisp and clear, sometimes vague and nebulous. Rarely consistent, often disputed, it binds us together and drives us apart. Some of us view the past through rose tinted spectacles; others see it through clouds of gloom. ‘Recollections may vary.’

And because of all this, memory is a prime source and subject for creativity.

'To me a poem is not a forever thing, nor the statement of long held views, but the product of a moment so suddenly and hurtingly felt that it has to burst out into words.'

Molly died in 1993 and was buried in Tanworth-in-Arden, alongside her husband and son. Early on the morning of Christmas Day 1992, her last Christmas, she had written the following stanza:

‘Amid the unceasing starts and flurries

My heart is busy at its usual game,

The manufacturing of woes and worries

Lest the serene of life should seem too tame.’

‘We strolled the Spanish marketplace at ninety in the shade,

With all the fruit and vegetables so temptingly arrayed,

And we can share a memory as every lover must,

And I remember oranges,

I remember oranges,

I remember oranges,

And you remember dust.

The autumn leaves are tumbling down and winter's almost here,

But through the Spring and Summer time we laughed away the year,

And now we can be grateful for the gift of memory,

When I remember having fun,

Two happy hearts that beat as one,

When I had thought that we were we,

But we were you and me.’

Molly Drake, ‘I Remember' (Song)

No. 508