Triumphing over Torture: A Lesson from Saint Lawrence at the Courtauld Gallery

Saint Lawrence by the Master of the Fogg Pieta

I recently visited the newly refurbished Courtauld Gallery in London.

It’s a joy to wander up the elegant spiral staircase, through light, open rooms with ornamental plasterwork, to admire again the fabulous collection of masterpieces from medieval to modern times.

I have always particularly enjoyed medieval galleries. The glistening gold of the altarpieces, the florid decoration of the illuminated manuscripts, the defiance of perspective. The arcane symbolism, the demons and devils, the obscure stories of intrepid saints, tragic martyrs and devout patrons.

This time my attention was drawn to a fourteenth century painting of Saint Lawrence by the Master of the Fogg Pieta. Lawrence is shown with neatly groomed hair in his blue clerical outfit. He carries a red book in one hand and a large iron griddle in the other.

Lawrence was a Deacon of Rome in the third century and had particular responsibility for overseeing the church’s property and possessions. When the Emperor Valerian determined to suppress Christianity, his Prefect in Rome demanded that Lawrence hand over the church’s wealth. Lawrence quickly distributed the assets to the poor, and, after three days, reported to the Prefect with a group of the old, infirm and impoverished. These people, he declared, were the true treasures of the church.

The Prefect was so angry that he had Lawrence strapped to a gridiron and roasted over hot coals. In the middle of his ordeal Lawrence cheerfully cried:

'I'm well done on this side. Turn me over!'

Lawrence was subsequently appointed patron saint of cooks and comedians.

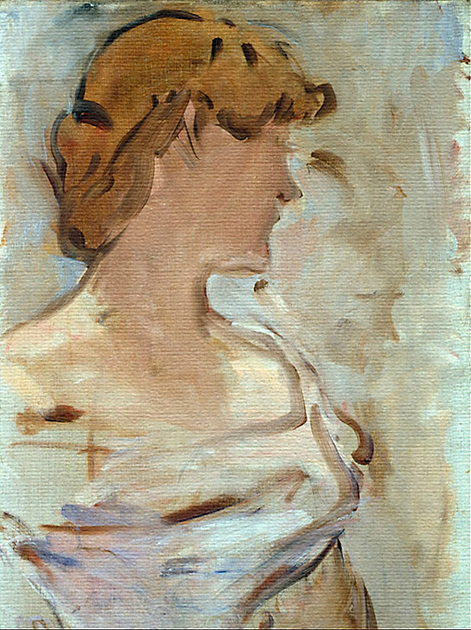

Saint Stephen by Carlo Crivelli

There’s something of a tradition in medieval art of depicting martyrs with the instruments of their torture and death. Saint Stephen is painted with the stones that killed him, Peter the Martyr with a cleaver in his head. Saint Catherine is shown with the breaking wheel to which she was submitted, Apollonia with the pliers that removed her teeth. (She is the patron saint of dentists.) Saint Bartholomew is presented holding aloft his own skin. He was flayed to death.

'The tyrant dies and his rule is over, the martyr dies and his rule begins.'

Soren Kierkegaard

St Catherine of Alexandria. Vittore Crivelli (c.1444–1501 or later)

I have occasionally reflected that if I had my portrait painted I would like to be accompanied by the instruments of my own professional torture. A set of timesheets perhaps, to recall the tedious pressure to make sense of the working week. Or a bowl of M&Ms, to commemorate the hours spent watching focus groups. Or a set of traffic lights, to indicate the persecution of pre-tests. Or a flip chart, or a Diet Coke, or an ice-breaker exercise (not sure how to represent this). Or that costume they made me wear for a team-building task.

'It is the cause, not the death, that makes the martyr.’

Napoleon Bonaparte

The martyrs of yore may have a lesson for us today. Theirs is a story of belief and perseverance. Sustained by their unwavering faith, they triumphed over torture. They defeated death.

If we can maintain our belief in the power of creativity and the primacy of the idea - if we can hold tight to our principles and keep our eyes on the prize - then surely we can overcome our daily trials and tribulations, the grinding pressure to compromise and concede, the gravitational pull towards sensible mediocrity. We can become martyrs to the work.

'At school they taught me how to be

So pure in thought and word and deed.

They didn't quite succeed.

For everything I long to do,

No matter when or where or who,

Has one thing in common too.

It's a, it's a, it's a, it's a sin.’

The Pet Shop Boys ‘It’s a Sin’ (C Lowe, N Tennant)

No. 358