Bonnard: Liberating Oneself from the Literal

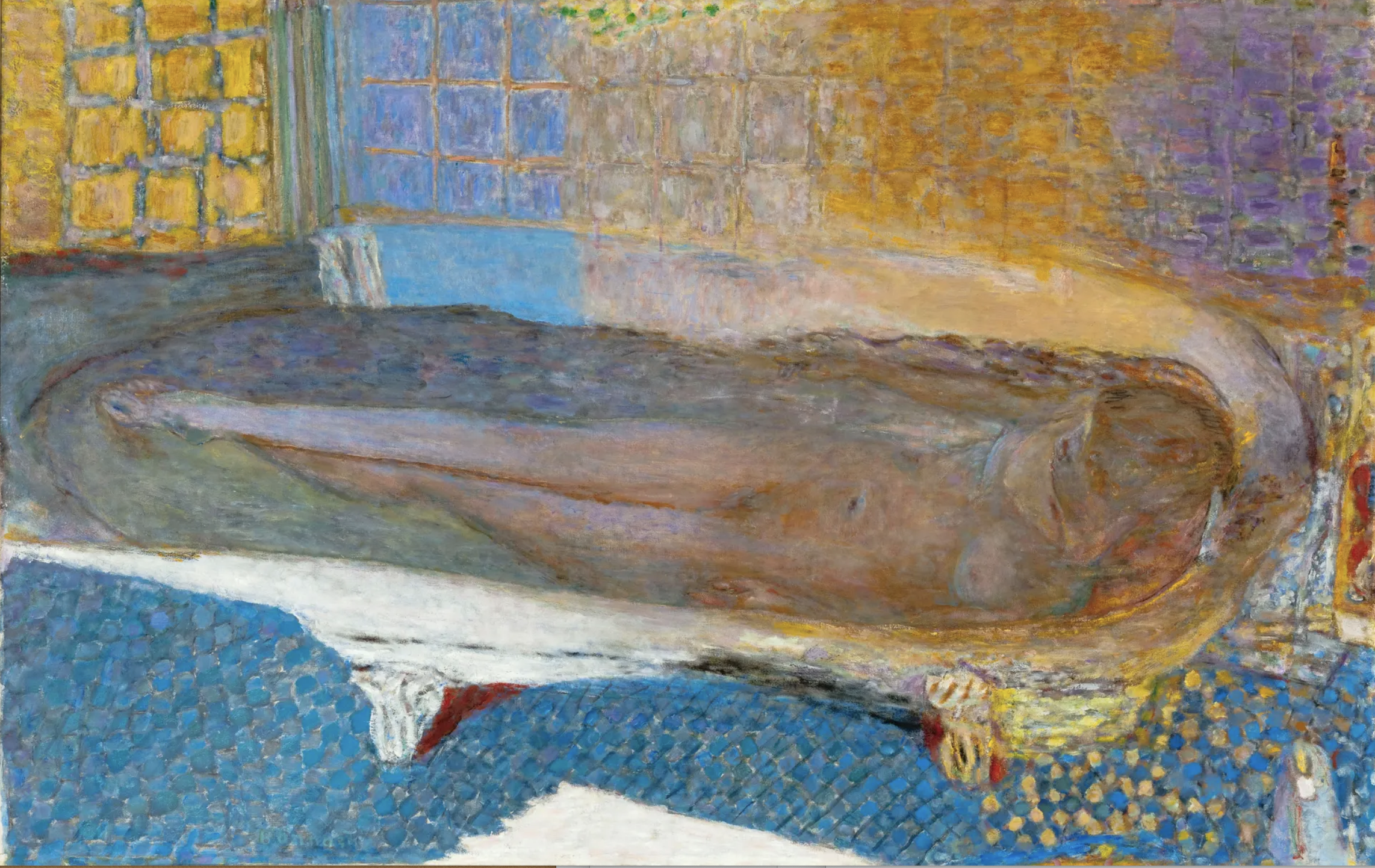

Pierre Bonnard’s Nude in the Bath, 1936. Photograph: Tate

‘I leave it…I come back…I do not let myself become absorbed by the object itself.’

Pierre Bonnard

I recently visited an exhibition of the work of French Post-Impressionist painter, Pierre Bonnard (Tate Modern, London until 6 May).

The table is laid with a red gingham cloth. There is fruit, a water jug, a coffee pot. The dog perches. We see a vase of flowers, a bowl of lemons, of peaches, a notebook and pen. Amber walls. Summer heat. The door to the garden is open. A lush lavender landscape reaches out to us across that table, through the French windows. A sun-drenched vista of greens and yellows beckons beyond that open door. A vibrant exterior life viewed from a secluded interior.

A woman is observed in the mirror on the mantelpiece. Her head turned away, looking past us and through us. A woman absorbed in her grooming, scrubbing her neck, pinning her hair. A woman framed by a bathtub, illuminated by the brightly coloured tiles, distorted by the water. It is as if we have just walked into the room.

We are invited into the intimate domestic world of the artist and his wife, Marthe - a world of silent companionship, of lethargy and ennui. Marthe passes the time with coffee and private thought. She nibbles at fruit and talks to the dog. She escapes to her bath - ‘the only luxury she had ever longed for.’ Often unwell, she has been prescribed daily water treatments to soothe her.

Renowned for his sunny landscapes and vivid colours, Bonnard is sometimes described as a ‘painter of happiness.’ But he himself is not so sure:

‘He who sings is not always happy.’

Indeed Bonnard seems somewhat removed - a man withdrawn, observing his home and home-life from a distance, through a window or doorway, across a table; through bands of colour, layers of memory. Figures are like ghosts. They move in and out of focus, in and out of frame. Self-portraits seem anxious, mournful.

'One always talks of surrendering to nature. There is also such a thing as surrendering to the picture.'

Occasionally Bonnard employs photography, not as a record of actuality, but rather to bring to mind natural, informal poses; to suggest incidental occasions, snapshots of time.

Bonnard describes himself as ‘the last of the Impressionists’, and he does indeed paint impressions – recollections of lost moments, remembrance of things past. He works in the studio, from memory rather than from life. Taking months and sometimes years to complete a canvas, he lets his imagination recreate events; frees his intense pigments to dissolve into one another; allows colours to take over from objects, patterns to take over from people, ideas to take over from accurate representation.

‘The presence of the object…is a hindrance to the painter when he is painting. The point of departure for a painting being an idea.’

There is a lesson for us all here.

Of course, brands often have to reside in a real world of cold calculation and rational reflection. But the best brands can also abstract themselves from reality, liberate themselves from the literal. They inhabit a landscape of impressions, feelings, moods and colours; a place of emotional truth, of memories, dreams and desires; the world as we recall it, as we imagine it, as we want it to be.

Sometimes, like Bonnard, we need to learn to let go.

'So far away from you, and all your charms,

Just out of reach of my two empty arms.

Each night in dreams I see your face,

Memories time cannot erase.

Wide awake, and find you gone,

And I'm so blue, and all alone.

So far away from you, and all your charms,

Just out of reach of my two empty arms.’

Percy Sledge, ‘Just Out of Reach' (Virgil "Pappy” Stewart)

No. 219