When Everyone Talks and No-One Listens

It’s often said of the characters in Anton Chekhov’s plays that ‘everyone talks, but no one listens.’ The cast of feckless aristocrats inhabit a troubled world of melancholy, loss and ennui. They speak endlessly at each other of their dreams and disappointments, but they rarely pause to listen. Their relationships seem compromised by their own emotional deafness, their solipsism. They live lives of empty chat and listless languor, punctuated only by another trip to the samovar.

I wonder has the world of brand marketing something in common with Chekhov’s? Could modern brands be accused of speaking without listening? Talking loud, but saying nothing? Always on project, never on receive? Do they sometimes come across as egocentric and emotionally needy?

Sign up, sign in, sign on. Check in, check out. Like me, friend me, share me. Blipp me, bookmark me. Rate me, recommend me. QR code me. Upload me, download me. Facebook me, fan me. Tweet me, re-tweet me. Hashtag why?

There’s a tremendous assumption in much current marketing that consumers have infinite time and attention to dedicate to brands, regardless of the category they represent or the content they serve up for them. With a wealth of new media channels available to us, it’s often easy to confuse talking with conversation, to mistake interaction for a relationship. And as long ago as the nineteenth century the writer HD Thoreau was observing,’We have more and more ways to communicate, but less and less to say.’

In my experience strong relationships tend to start with a little humility and self knowledge. The best advice for brands seeking a relationship might be: don’t talk too much and only talk when you have something to say.

But can contemporary brands really be accused of not listening? Surely all serious players nowadays manage substantial research and insight programmes. Surely we’re endlessly soliciting feedback, measurement and learning?

Well, yes, but are brands engaged in the right kind of listening?

To my mind much of modern research practice could be deemed ‘submissive listening’. ’Hello. What do you think of me? What do you think of how I look and what I do? How would you like me to behave? Do you like what I’m planning to say to you? What would you like me to say?’

Is this the stuff of a healthy relationship? Surely brands’ engagement with consumers should begin from a position of equality and mutual respect, not submission and deference.

You’re equal but different.

You’re equal but different

It’s obvious.

So obvious.

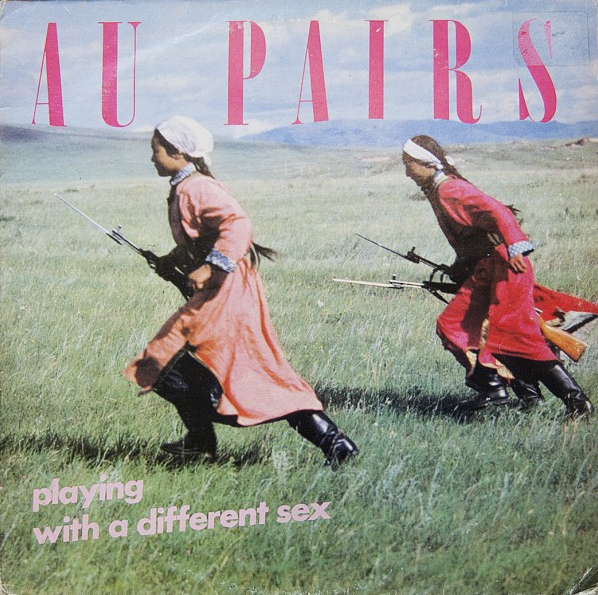

Au Pairs, It’s Obvious.

We could also categorise much of our research as ‘reflective listening’: recording what people say, wear, like and do, so that brands can play it back later to them in communication. There’s an underlying assumption that consumers empathise with brands that share their values and outlook on life. I’m sure they do. But one man’s insight is another man’s cliche. And reflective listening, interpreted literally, often produces communication that is curiously unrewarding. Because dialogue is more than elegant repetition and relationships are more than an exercise in mimicry.

Surely listening and talking should exist in close proximity and dynamic relation to each other. It’s called a conversation. And you’ll find spontaneous, instinctive, organic conversations at the heart of any healthy, happy relationship.

Of course, the hyper-connected, real time world of the social web affords us an opportunity. It’s the opportunity to demolish the distance between listening and talking; to inspire conversations between brands and consumers; and thereby to create vibrant, enduring, sustainable relationships. It’s now possible for listening to drive brands’ thought and action, tempo and timing and we we should all be striving to put it back at the centre of our communication models.

There is, nonetheless, a nightmare scenario. What if brands continue to propel their mindless chatter through the infinite arteries of the electronic age, without respecting our audience’s limited time and attention? What if our attempts to listen continue to betray a submissive and reflective orientation towards consumers?

At the end of Chekhov’s Three Sisters, twenty year old Irina decides to give up on love before love gives up on her.

'I’ve never loved anyone. I dreamed about it for a very long time – day and night – but my heart is like a piano that’s been locked up and the key is lost.'

It’s one of the saddest lines in theatre. I worry that if we don’t start listening properly to consumers, then consumers will stop listening to us.

First Published in Hall & Partners magazine, Matters.

No. 24