‘Are You Together?’: Is Your Business Like a Team or a Family?

It was a busy Friday evening at the Fish Central takeaway counter. I’d made my usual order - cod, chips and mushy peas - and was waiting to one side for the fish to fry.

Next up in the queue was a track-suited man in his mid 40s.

‘Scampi and chips please, with a couple of onion rings.’

Behind him was a woman of a similar age, with a child alongside.

‘Just two small cod and chips for us.’

The Cypriot chap taking the orders at the till looked up at the man and woman.

‘Are you together?’

They regarded each other wearily. ‘Yes, we’re together,’ replied the track-suited man.

Then he retreated to where I was waiting by the window and muttered under his breath: ‘Just about.’

The woman could tell he’d made a sarcastic remark.

‘What’s that you said?’

‘Oh, nothing, dearest….’

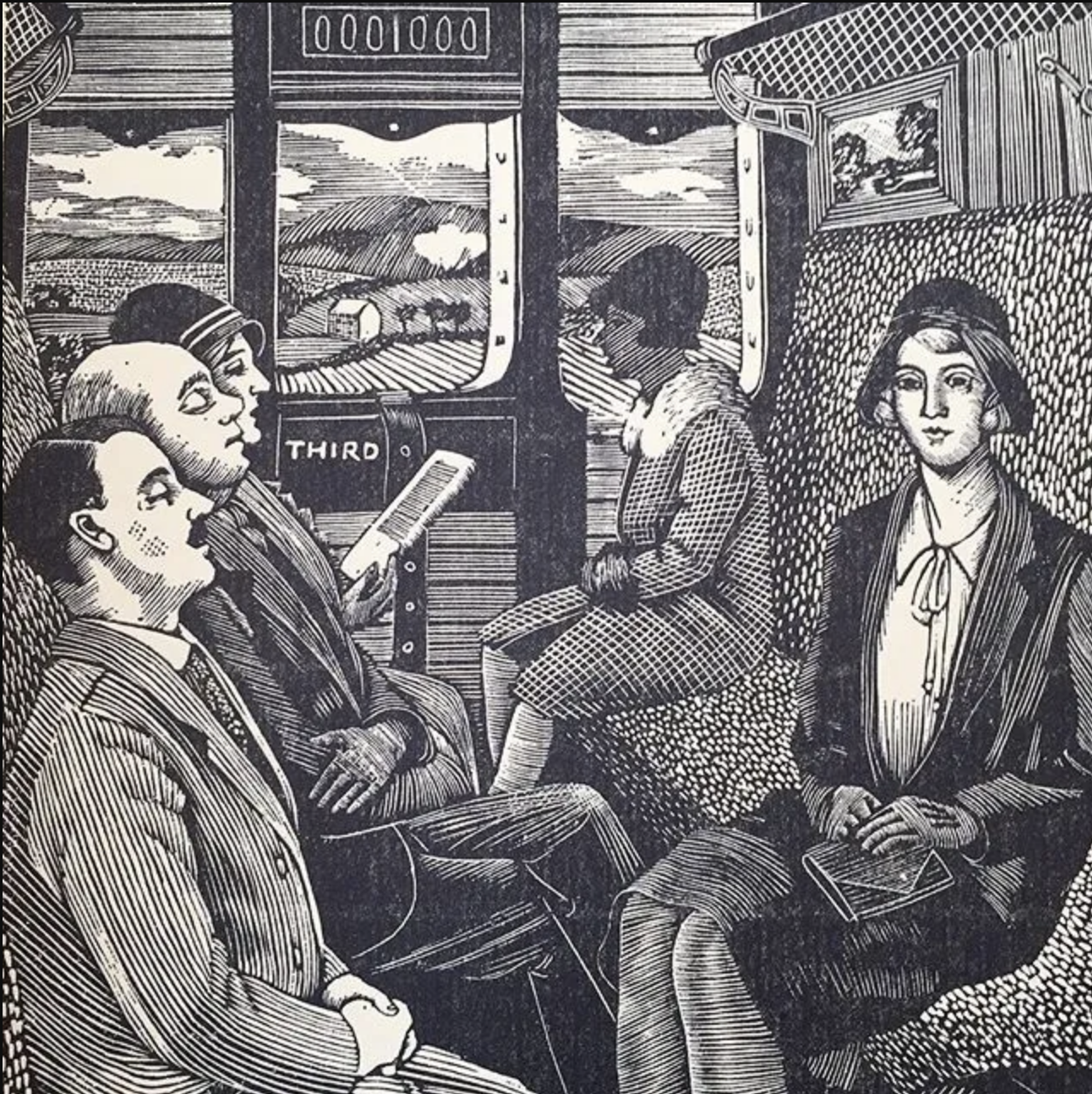

This exchange prompted me to speculate on the nature of the family’s relationships. I imagined the couple had been an item for some time. They’d got past romantic gestures and displays of affection. They were now familiar with each other’s faults and foibles, and were enjoying subtle digs and droll remarks. The kid seemed entirely comfortable with their sharp words.

'The family – that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape, nor, in our inmost hearts, ever quite wish to.'

Dodie Smith, Novelist and Playwright

In corporate life we often see ourselves as creating high-performance sports teams. The leadership challenge is characterised as managing a diverse set of talents and personalities; organising them to function optimally, day-in, day-out; encouraging them to work towards a single unifying goal. We promote players who excel; drop them to the bench if they’re out of form; transfer them if they don’t improve.

This is certainly a useful way of framing the task. But I sometimes find sport analogies a little clinical, somewhat two dimensional.

Real life and real commerce are, in my experience, a good deal more messy than this.

'Feelings of worth can flourish only in an atmosphere where individual differences are appreciated, mistakes are tolerated, communication is open, and rules are flexible - the kind of atmosphere that is found in a nurturing family.’

Virginia Satir, Clinical Social Worker and Psychotherapist

The best businesses also have something of the family about them. The core members have enjoyed the good times and endured the bad times together. They have rolled with life’s punches, learned to accommodate each other’s shortcomings and eccentricities; to acknowledge rivalries and accept differences. The relationships are complex and varied. The conversations are frank and open. The hierarchies are arcane and mysterious. They have been bound together by emotional ties of shared experience and values that date back years. They are fiercely loyal to each other.

Of course, analogies only go so far.

Once home, I liberated the cod and chips from its paper wrapping, poured the mushy peas to one side of the heated plate and sprinkled the dish with salt, dousing it in vinegar. Alone tonight, I dined from a tray and watched football on TV. And I washed the feast down with a glass of cold Chablis.

‘Haven't you noticed

A breakdown in the family tie?

Just not as strong as it once was,

Every time I see it weaken, it makes me want to cry.

Oh, what a shame,

Because another home's falling apart.

Oh, what a shame,

Another group of broken hearts.

It's not a secret,

We all know that it's slipping away.

Don't let it go, no, don't you let it go.

It is the only true foundation on which we can survive.

Don't be afraid,

Because you got to take it for a stand.

Don't be afraid,

You've got to try to understand.

Bring the family back, bring it back together.

Bring the family back,

Bring the family back, bring it back together,

Together.’

Billy Paul, ‘Bring the Family Back’ (F Smith / T Phillip)

No. 509