Edward Burra: Cultural Immersion

Edward Burra - Dockside Cafe, Marseilles, 1929, © Estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd, London

I recently enjoyed an exhibition of the work of Edward Burra. (Tate Britain, London until 19 October)

Burra painted satirical watercolours of French bohemians in the Roaring Twenties and the vibrant club scene during the Harlem Renaissance. He painted unsettling images of Spain as it descended into civil strife, and East Sussex in turmoil during World War 2. After the conflict, he painted British landscapes disfigured by industry and commerce. He had a knack for finding the nexus of social and historical change, immersing himself in culture, directing his acute eye to human foibles and foolishness.

Burra was born in London in 1905 into a wealthy banking and legal family. Diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and suffering from anaemia, he turned to painting as ‘a kind of drug’ that relieved the pain. He found it was physically easier to work with watercolours flat on a table, rather than with oils at an easel.

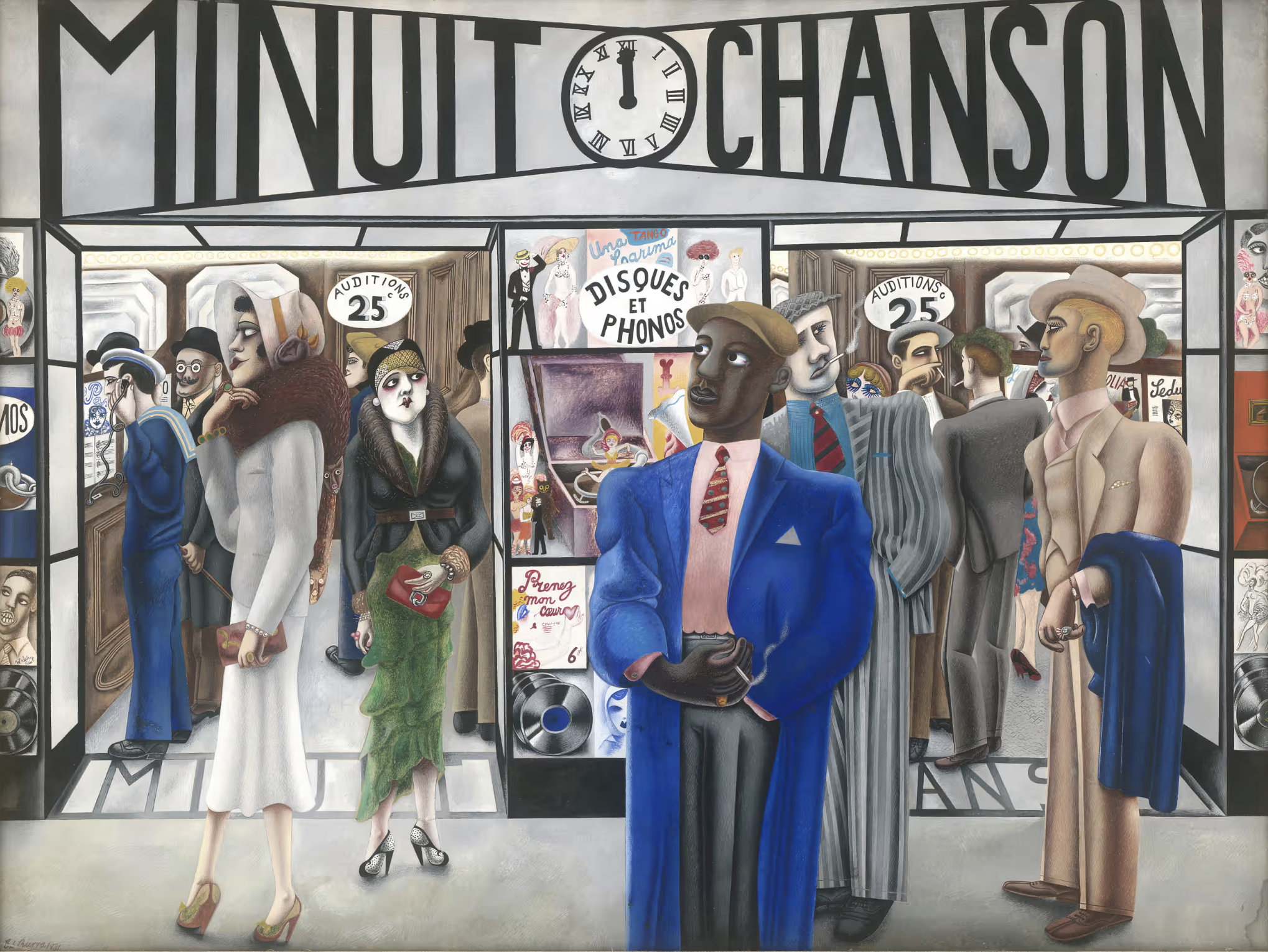

Edward Burra - Minuit Chanson, 1931. Photograph: © Estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd, London

Having studied at Chelsea Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art, Burra, who had learned French at an early age, travelled to Paris. He visited the museums and galleries; feasted on the cinema, literature and music; soaked up the cosmopolitan nightlife in the cafes and clubs of Montparnasse and Montmartre; took trips to the sunny south, to Marseille, Toulon and Cassis.

We visit a mirrored dancehall, an underground gay bar, a grubby dockside hangout - where high-society smoothies rub shoulders with shady lowlife and flat-capped gangsters. Bobbed women in cloche hats and dark eye-shadow chatter conspiratorially, hold cigarettes nonchalantly, down cocktails eagerly - at Le Café du Dome, Le Select, Le Boeuf sur le Toit. Eager customers crowd into the listening booths at the new record store on Boulevard Clichy. Burlesque dancers serve at the teashop. Uniformed sailors stand chatting to the diffident attendant. It's all rather emancipated, permissive, decadent.

In 1933 Burra sailed to New York and stayed in Harlem for several months. (He would return throughout the ‘30s and ‘50s.) He was besotted with the nightlife, drinking and dancing; with Club Hot-Cha, the Apollo Theatre and the Savoy Ballroom. He collected 78 RPM records and would listen to jazz while he painted - to McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, Cab Calloway and Clarence Williams; to Billie Holliday, Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald. In his work he captured the syncopated glamour of the band; the joyful strutting on the dancefloor. He portrayed people hanging out on the doorsteps of brownstone tenements, a train passing by on the elevated railway.

Burra’s pictures were not always accurate records of reality. Rather he freely integrated his memories with his imagination.

‘When I go back there, I’m always puzzled by what I’ve left out.’

Edward Burra - Harlem 1934, © Tate

An independent spirit, one afternoon he walked out on his family home in Rye without saying a word. His parents only discovered he had been in the United States when he returned weeks later.

In the 1930s Burra travelled to Spain, visiting Barcelona, Grenada, Seville and Madrid. Again he immersed himself in the country’s art, literature and music. And again he learned the language. Inspired by Spain’s history and tradition, he painted strutting matadors and proud flamenco singers, austere governesses and sophisticated society hostesses. But he also became aware of the tensions on the street as Civil War loomed. Initially sympathising with the Fascists, his work grew darker and more surreal. The Grim Reaper, demons and the Devil stalk the cityscape, overseeing destruction and decay.

Edward Burra - War in the Sun

At home in Sussex during World War 2, with his medicine rationed and his movement restricted, Burra felt isolated, hemmed in. His paintings stayed depressed and downbeat. We are shown a claustrophobic world, distorted by trucks and military paraphernalia, crowded with soldiers in sinister carnival masks.

Burra was an elusive character. Garrulous and gossipy with his friends, he was guarded and reticent with strangers. He rarely gave interviews, and he refused to explain his art.

Burra: I never tell anybody anything… So they just make it up. I don’t see that it matters.

Interviewer: What does matter?

Burra: Nothing.

Looking back on Burra’s artistic journey, I was struck by his ability to locate himself in the hotspots of cultural change. He regarded what he found with a mixture of affection and cynicism; with the acuity of an eternal outsider. He teaches us to seek out the melting pots, the frontiers and borderlands; to learn the language and soak it all up; to participate and yet retain some distance.

In the 1960s, as Burra’s frail health deteriorated further still, he took long driving tours of Britain with his sister Anne. Once more, he was alert to change. Whilst depicting the beautiful hills, valleys and moorland that he saw through the windscreen, he also recorded the power stations, pylons and petrol stations; the motorways, diggers and brash advertising hoardings. This was an uneasy landscape, a countryside in distress. He was an early prophet of environmental decay.

Burra died in 1976, aged 71.

Edward Burra - Picking a Quarrel, 1968-69 © Estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art Ltd, London

'I'm just a woman, a lonely woman,

Waiting on the weary shore.

I'm just a woman that's only human,

One you should be sorry for.

Woke up this morning alone about dawn.

Without a warning I found he was gone.

How could he do it? Why should he do it?

He'd never done it before.

Am I blue? Am I blue?

Ain't these tears in these eyes telling you?

Am I blue? Why, you'd be too.

If each plan with your man done fell through.’

Ethel Waters, ‘Am I Blue?’ (H Akst, G Clarke )

No. 525