Frida Kahlo: ‘I Paint My Own Reality’

“Self-Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace” by Frida Kahlo. By Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

I recently watched a thoughtful documentary about the life and work of artist Frida Kahlo. (‘Frida Kahlo’ 2020, directed by Ali Ray)

Kahlo painted magical realist works that were forthright, beautiful and challenging. And she created a unique identity that was resilient, independent and inspiring. Having endured extraordinary physical and mental turmoil, she demonstrated how creativity can be a vehicle for making sense of one’s suffering. It can be a means of survival.

'I am my own muse. I am the subject I know best. The subject I want to know better.'

Frida Kahlo was born in 1907 and grew up in Coyoacán, a fashionable suburb of Mexico City. Her father was German and her mother was of mixed indigenous and Hispanic descent. She suffered from polio as a child and consequently her right leg was shorter than her left. The condition gave her a limp and an enduring sense of difference and isolation.

'Don’t build a wall around your suffering. It may devour you from the inside.'

Kahlo was admitted to a good school, thrived at the sciences and was on track to becoming a doctor. However at 18 she was involved in a terrible road accident - a tram crashed into the bus on which she was travelling home. She broke her spinal column, collarbone, ribs and pelvis, and had 11 fractures in her right leg. Her right foot was dislocated and crushed, and her shoulder was put out of joint. The incident sentenced her to a lifetime of pain, surgery, medical corsets and leg braces.

In the months immediately after the accident, Kahlo resumed her childhood interest in art. A mirror was installed above her sick bed so that she could paint at a special easel while lying on her back.

'The most powerful art is to make pain a healing talisman.’

In 1927 Kahlo joined the Communist Party, through which she met the painter Diego Rivera. He was a key figure in the Muralist movement, which, in the wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), sought to establish a new national art form by drawing on indigenous, pre-Hispanic culture. The couple married in 1929 and in the early 1930s travelled together in the United States.

'The most important thing for everyone in Gringolandia is to have ambition and become 'somebody,' and frankly I don't have the least ambition to become anybody.’

Eager to set herself apart from conventional American society, Kahlo adopted native Tehuana dress: braided hair, colourful embroidered blouses and long floral skirts. Her art also underwent a transformation. She rejected European traditions and, inspired by Mexican folk culture, created work that was intentionally naïve. Her pictures told stories in the style of votive paintings: small devotional works on metal (to protect them while hanging from damp walls), typically depicting a dangerous incident and the survivor’s gratitude.

'At the end of the day we can endure much more than we think we can.’

Henry Ford Hospital, 1932 by Frida Kahlo

In 1932, while living with Ribera in Detroit, Kahlo suffered a miscarriage. She subsequently recorded the event in ‘Henry Ford Hospital.’

Kahlo lies naked on a hospital bed, tethered by red threads to a piece of medical equipment, a teaching model of the female reproductive anatomy, a pelvis bone and her unborn foetus. She is weeping.

'My painting carries with it the message of pain.'

Kahlo and Ribera returned to Mexico, but their relationship was turbulent. He was consistently unfaithful and she had affairs with, amongst others, the exiled Leon Trotsky. She also turned to drink.

‘I drank to drown my sorrows, but the damned things learned how to swim.'

In 1939 the couple divorced, but remarried a year later. Soon after the separation, she painted ‘The Two Fridas’ (1939): two versions of herself sit side-by-side, holding hands against a stormy sky. One is in white European dress, the other in colourful Tehuana costume. Both have their hearts exposed, and they are connected by an artery. Mexican Frida, with a healthy heart, grips a small portrait of Rivera. European Frida, with a broken heart, clasps forceps and has blood from a severed vein spattered over her dress.

'There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the tram, the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.'

Frida Kahlo, Heart to heart … The Two Fridas (detail) 1939.

Photograph: Museo de Arte Moderno/De Agostini Picture Library/G Dagli Orti/Bridgeman Images

Kahlo created 150 paintings over her lifetime, of which a third were self-portraits.

She stares out from these pictures, unsmiling and resolute, usually with her head at a three quarters angle. Her distinctive unibrow and the hair on her upper lip defy stereotypes of beauty. While her face remains fixed, the elements around her change. There are ribbons, flowers and braided crowns; dogs, spider monkeys, parrots and butterflies. There’s lush vegetation and a dead hummingbird suspended from a thorn necklace. It is as if she is saying: I am consistently me, but I am endlessly complex.

'I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.'

'What the Water Gave Me' (1938) presents Kahlo’s pictorial biography from her perspective in a bathtub. Her legs and feet stretch out before us and on the surface of the grey water we see an empty Mexican dress, a seashell full of bullet-holes, the artist’s parents and two female lovers. There’s a skyscraper bursting forth from a volcano, a dead woodpecker and a small skeleton resting on a hill. A faceless man holds a rope that throttles a naked female figure in the distance.

It’s as if we are being invited to share Kahlo’s bath; to witness her darkest private reflections.

'Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?'

Frida Kahlo, What the Water Gave Me

Kahlo was not prepared to be boxed-in or categorised. In the same year as she painted 'What the Water Gave Me' the leading surrealist writer, Andre Breton, visited Mexico and pronounced her pictures ‘pure surreality.’ But she maintained her independence from any art movement.

'They thought I was a surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.'

Kahlo returned again and again to the theme of her pain.

In ‘Broken Column’ (1944) she painted her spine as a classical column, cracked and fragmented. Standing in a barren landscape, she is naked but for a white skirt and metal corset, her face and body pierced by nails. Again she is weeping. But her gaze is defiant, resolute - like a martyr.

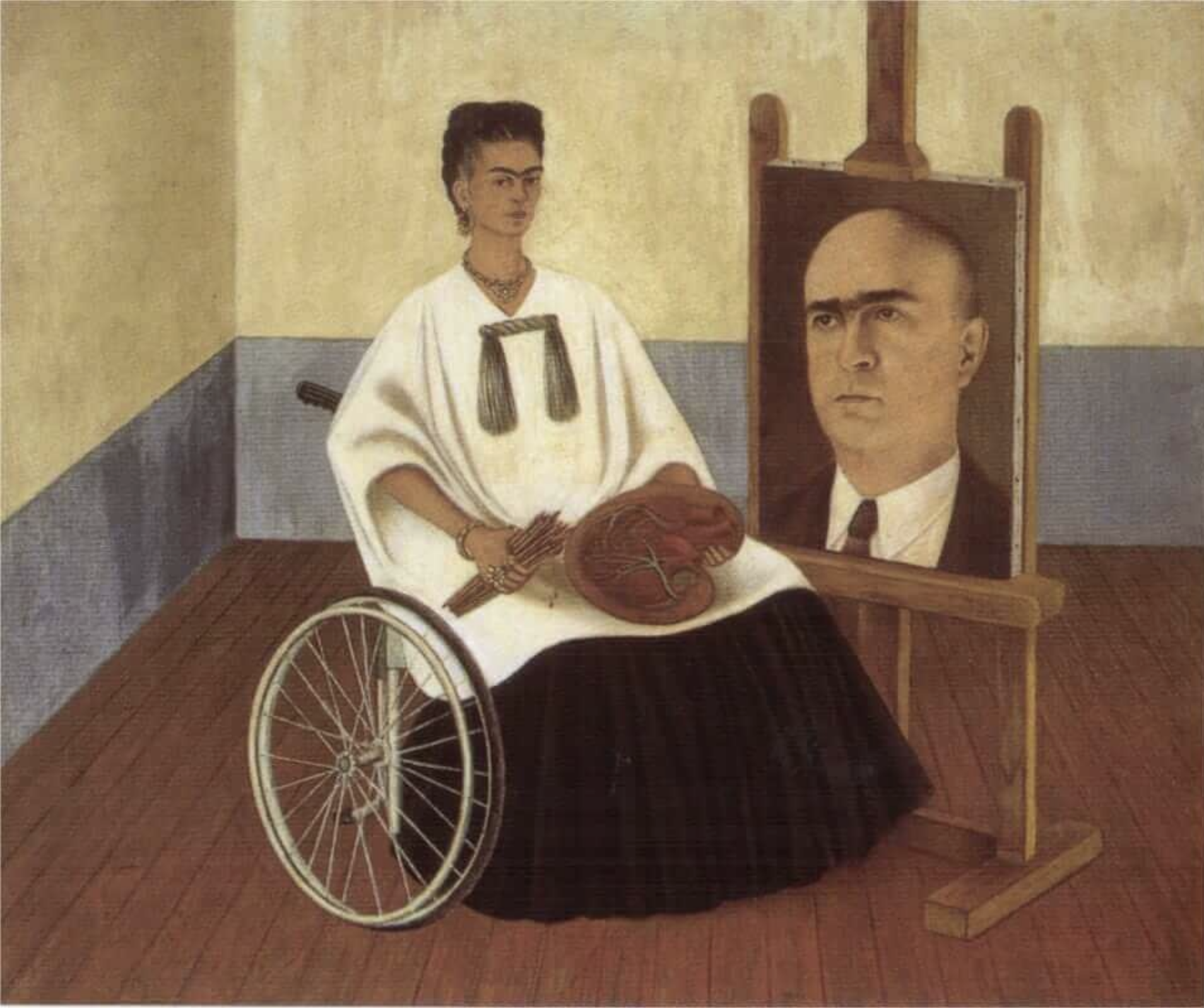

Self Portrait with the Portrait of Doctor Farill, 1951 - by Frida Kahlo

In her last signed self-portrait, ‘Self Portrait with the Portrait of Doctor Farill’ (1951), Kahlo depicts herself in her wheelchair alongside a painting of the surgeon who that year had performed seven operations on her spine. Her palette carries the image of a heart and her brushes drip with blood.

'Passion is the bridge that takes you from pain to change.'

Clearly Kahlo used her art to provide some relief and distraction; to understand her pain; to navigate her sadness. ‘The only way out is through.’

In the 1950s Kahlo's health deteriorated further. In 1953 she had her first solo exhibition in Mexico, and she died the following year. She was 47.

After her passing, Kahlo became an icon of individuality. She was admired and adored for her fierce resilience and independence; for her beautiful mind; for painting her own reality.

'I used to think I was the strangest person in the world. But then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me, too.’

'Across the evening sky, all the birds are leaving.

But how can they know it's time for them to go?

Before the winter fire, I will still be dreaming.

I have no thought of time.

For who knows where the time goes?

Who knows where the time goes?

Sad, deserted shore, your fickle friends are leaving.

Ah, but then you know it's time for them to go

But I will still be here, I have no thought of leaving.

I do not count the time.

For who knows where the time goes?

Who knows where the time goes?

And I am not alone while my love is near me.

I know it will be so until it's time to go.

So come the storms of winter and then the birds in spring again.

I have no fear of time.

For who knows how my love grows?

And who knows where the time goes?’

Sandy Denny, ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes?’

No. 463