Merce Cunningham: ‘The Surprise of the Instant’

Gerda Peterich, Merce Cunningham Courtesy of the Barbican

‘Dancing exercises on dancers an insidious attraction that makes them work daily at perfecting an instrument which is really deteriorating from birth.’

Merce Cunningham

I recently watched a fine documentary about the American dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham (‘Cunningham’ by Alla Kovgan).

Cunningham liberated dance from established practice and historic convention. He celebrated the infinite possibilities of human movement. His dance was precise and complex, intensely physical and intellectually rigorous. He collaborated across media and embraced the creative potential of chance, technology and the absurd. He redefined the way people think about dance. And he always resisted definitions.

‘Are you an avant garde choreographer, a maker of modern dance?’

‘Oh, I’m a dancer. That’s sufficient for me.’

Let us consider some of Cunningham’s core principals.

‘Everybody in the audience is different. So they may all dislike it. But they dislike it for different reasons.’

1. ‘The Only Way to Do It Is to Do It.’

Cunningham was born into a family of lawyers in Centralia, Washington in 1919. Having learned tap as a young boy, he studied acting and then dance at the Cornish School in Seattle. In 1939 he moved to New York and danced as a soloist in the Martha Graham Dance Company for six years. In 1944 he presented his first solo show, and in 1953, while teaching at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, he formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

‘The only way to do it is to do it.’

Success did not come easy to the company. In the early days they would tour America in a VW Camper Van. On one occasion they arrived at a gas station, piled out of the bus and started limbering up. The attendant enquired:

‘Are you a group of comedians?’

‘No, we’re from New York.’

Gerda Peterich, Merce Cunningham, 1952. Courtesy of Fall for Dance North

2. Expand Your Vocabulary

Cunningham was concerned with all forms of movement. He liked to set up oppositions – between, for example, a slow arm and a rapid foot. His dancers twisted and turned, jerked and juddered; they slid, skipped, squatted and stretched. Their actions were sometimes beautiful and sometimes on the edge of awkward.

‘My idea about movement is that any movement is possible for dancing. That ranges all the way from nothing of course, up to the most extended kind of movement that one might think up.’

3. Broaden Your Perspective

Cunningham was not interested in the conventions associated with ‘putting on a show.’ He distributed his dancers across the whole stage and oriented them at every angle – eschewing the ‘front and centre’ spot and its associated hierarchies, denying the audience a focal point on which to settle their gaze.

'What really made me think about space and begin to think about ways to use it was Einstein's statement that there are no fixed points in space. Everything in the universe is moving all the time.’

Merce Cunningham Dance Company in Cargo X, 1989Photography by Jed Downhill

4. ‘Don’t Interpret. Present’

Cunningham wanted his dance to be autonomous, and so his choreography was ‘non-representational.’ It did not refer to, or interpret, any historical event or mythical story; any particular feeling or idea.

‘We don’t interpret something. We present something. We do something. And then any kind of interpretation is left to anybody looking at it in the audience.’

5. Don’t Integrate. Liberate

From the outset Cunningham worked with composer John Cage, who became his lifelong partner and frequent collaborator. They determined that music and dance should exist independently within the same performance. The dancers’ movements would no longer be harnessed to the rhythm, mood and structure of the music.

'I think the thing that we agreed to so many years ago actually, was that the music didn't have to support the dance, nor the dance illustrate the music, but they could be two things going on at the same time.’

6. Assimilate the Flaws

‘You have to allow for every body. Every single person has a possibility.’

While ballet had a tradition of elegant uniformity, Cunningham sought to accommodate individuality of body shape, personality and movement. Although he was incredibly precise and demanding, he saw creative opportunity in human differences and flaws.

‘I think that Merce was interested in what could be considered our flaws as dancers. And he hesitated to correct us unless he just got irritated by what he saw.’

Viola Farber, Dancer

‘He demands that you are first of all yourself as a human being, and from that a dancer.’

Gus Solomons Jnr, Dancer

Martha Graham with Merce Cunningham

7. Renounce Competition

In keeping with his embrace of individuality, Cunningham cultivated an egalitarian ethos within his company.

‘I myself never liked that competitive thing that so much of dancing seemed to have. So I never tried to do that in my own situation. I went on the assumption that each dancer was a person who had certain abilities. I would attempt to let each of the dancers find out for himself how he danced, what kind of person he was in that situation. It’s not politics. It’s dancing.’

8. Accept the Absurd

Cunningham was interested in challenging audiences with the surreal and the absurd.

‘People have often defended art on the grounds that life was a mess and that therefore we needed art in order to escape from life. I would like to have an art that was so bewildering, complex and illogical that we would return to everyday life with great pleasure.’

And so Cunningham presented a door on wheels and a man with a chair on his back. There was a woman with an illuminated umbrella and a chap struggling to put a sweater on. The stage was filled with silver pillows.

9. Embrace Chance

Recognising that chance is a critical component in ordinary life, Cunningham put it to work as a creative tool. Randomness could be used to break up traditional structures; to challenge conventional notions of narrative – beginning, middle and end. Randomness also freed his imagination from its own assumptions, counterbalancing his habits and rationality with the unplanned and the unexpected.

'The use of chance operations opened out my way of working. The body tends to be habitual. The use of chance allowed us to find new ways to move and to put movements together that would not otherwise have been available to us. It revealed possibilities that were always there, except that my mind hadn't seen them.’

Cunningham would flip coins, roll dice, turn playing cards or consult the I-Ching to determine the order of different steps or the sequence of different passages. Sometimes dancers were given a set of movements that they could execute as they pleased: in any order and with any frequency; exiting and entering at will.

10. Experiment with Technology

Cunningham experimented extensively with television, video and computers; with animation, body sensors and motion capture. Technology enabled him to overcome long-established limits of possibility; to re-imagine the human body and the process of dance creation.

'It expands what we think we can do. I think normally the mind gets in the way and says, 'You can't do that.”

11. Embark on ‘An Adventure in Togetherness.’

‘We have only two things in common: our ideas and our poverty.’

Robert Rauschenberg

Rather than seeking to impose a singular artistic vision, Cunningham enjoyed the alchemy of collaboration. As well as partnering with Cage, he worked with musicians David Tudor and Brian Eno; with fashion designer Rei Kawakubo; and with artists Robert Rauschenberg, Bruce Nauman, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella and Jasper Johns.

For Cunningham these partnerships represented ‘an adventure in togetherness.’

‘One of the most amazing things about our collaboration was sort of a carte blanche trust, where nobody is really responsible, but as a group of people we’re not irresponsible. And I think that creates a wonderful feeling about the possibilities of society.’

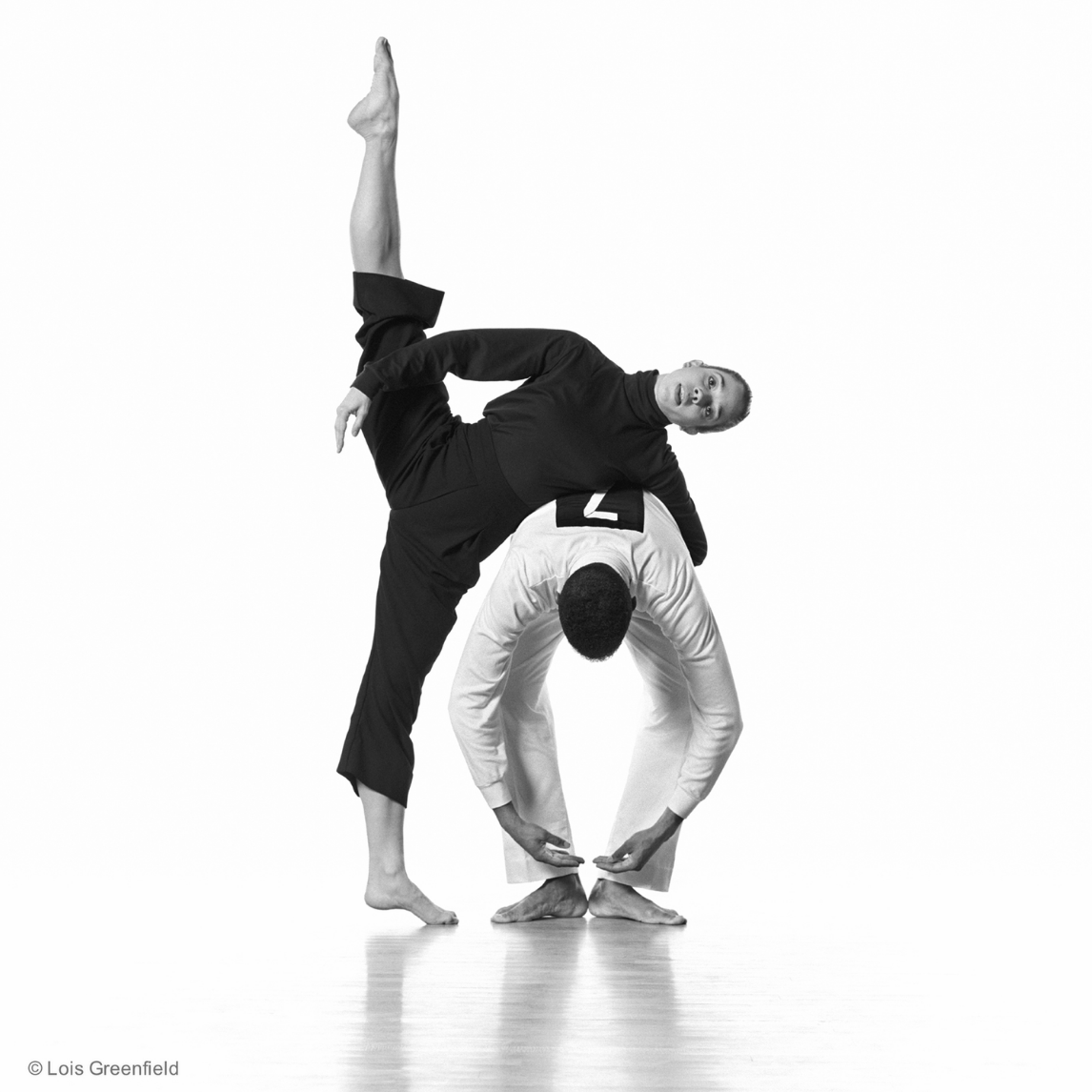

Breckyn Drescher and Christian Allen performing “Roaratorio” by Merce Cunningham.Credit: Andrea Mohin/The New York Times

12. ‘Believe in the Surprise of the Instant’

Over a 70 year career Cunningham choreographed some 180 dances and more than 700 site-specific events. He took his company all over the world and performed as a dancer into the early 1990s. In 2009 he presented ‘Nearly Ninety’, a piece that marked his 90th birthday. He died at his home in New York a few months later.

Cunningham encouraged us to reflect on the fundamentals of our endeavours; to be radical in our ambition and bold in our execution. And he sustained his enduring appetite for dance through ‘a continuous belief in the surprise of the instant.’

‘It is for me a question of faith, and a continuous belief in the surprise of the instant. Put aside fatigue, aches, injuries to the body and psyche. Let the shape and the time of a single or multiple action take its weight and measure. It will be expressive.’

'Soon as I get used to the pain,

Maybe then I'll understand why

Tears fall down like rain.

Tell me how can love seem so deep

And leave at the wink of an eye?

Surprise, surprise. Look what's falling out of my eyes.’

Bobby Womack, ‘Surprise, Surprise’ (B Womack, J Ford)

No. 327