The Amnesiac Industry: If We Have No Memory of the Past, We Can Have No Vision for the Future

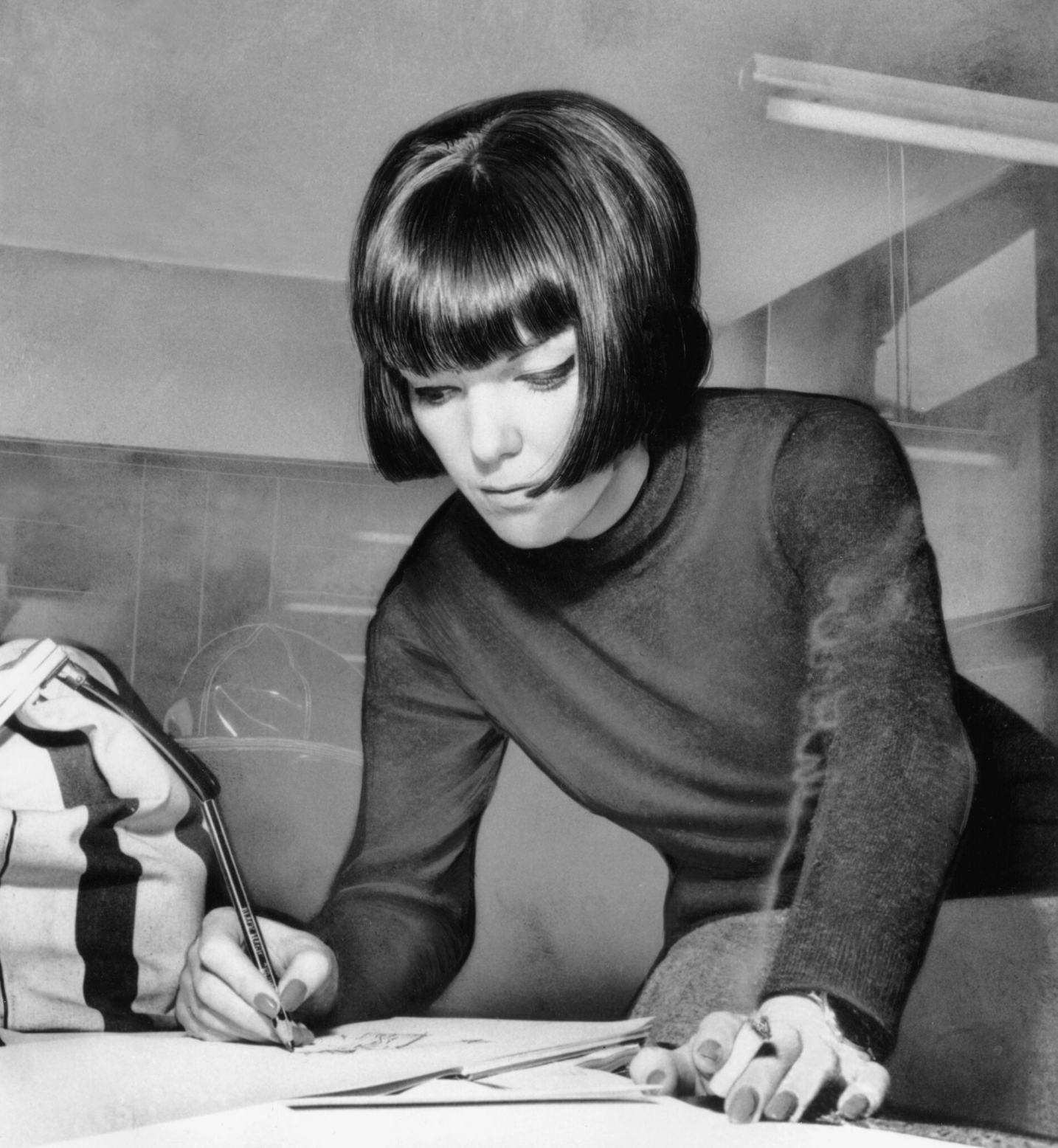

‘Mnemonic’ at the National Theatre Photo: Johan Persson

‘Mnemonic’ is a play about memory and migration, ancestry and storytelling. (The National Theatre, London, until 10 August).

The body of a man has been discovered under Tyrolean ice. It turns out to have been preserved for over 5,000 years. How did the Iceman get there? Where did he come from? Was he a shaman or a shepherd, a victim of a patriarchal challenge, or of a pogrom?

A woman disappears on the morning of her mother’s funeral. She has set off on an odyssey across Europe, in search of the father she never knew.

Her partner, left behind in London, desperately tries to make sense of it all.

A 1999 work by the Complicité theatre company, ‘Mnemonic’ was conceived and is directed by Simon McBurney. This imaginative, layered production uses props and visual effects to take us on a speeding train, into bars and bedrooms, and up to an Alpine ridge. We are invited to don a mask and feel a dead leaf. We meet migrants living in London suburbs. And an articulated chair plays a starring role. We are prompted to reflect on the interconnectivity of our pasts and futures; on the fundamental human need for narratives.

In particular, the play asks us to consider memory.

‘Memory is a pattern. Of electrical synaptic connections. Each time you remember, your brain has to re-make this pattern. It is a creative act, and it happens at a speed no computer can match. But the memory is different each time. And because the pattern can never be exactly the same, so it is… an imaginative act. Remembering is about discarding and choosing, forgetting and creating, losing and finding, dismantling and simultaneously re-making.’

Simon McBurney

‘Mnemonic’ begins with a discussion of a celebrated neuroscience case. (Also outlined in the Programme Notes by Daphna Shohamy, Professor of Brain Science at Colombia University.) In the 1950s a man underwent surgery for a severe condition of epilepsy. The surgeon removed his hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure behind each ear. The patient recovered well - his past memories, language, reasoning and sense of self remaining intact. But he lost the ability to create new memories.

‘[Subsequent research has established that] Patients with hippocampal damage struggle not just with new memories, but also with imagining the future. When asked to envision future events – such as plans for next weekend, or their next birthday party – their minds draw a blank.’

Daphna Shohamy

I was struck with this thought that our memories determine our capacity to imagine the future.

The communications industry proudly proclaims its talent for predicting, managing and creating change. It positions itself firmly in the future, always looking forward to the next horizon; to tomorrow’s world.

But it tends not to be so expert in the past, rarely reflecting on historic models, case studies and thinking; seldom studying the learnings of previous generations.

It is an amnesiac industry. And as such it is constrained in its ability to progress at pace, and cursed continually to re-make past mistakes.

I’d advise young strategists to be historians as much as forecasters. I’d encourage them to read Paul Feldwick’s analysis of how different eras have understood advertising effectiveness (‘The Anatomy of Humbug’); to consider old D&AD, APG and IPA Effectiveness annuals; to talk to veteran practitioners; to visit the History of Advertising Trust.

Because if we have no memory of the past, we can have no vision for the future.

'Did we give up too soon?

Maybe we needed just a little room.

Wondering how it all happened,

Maybe we just need a little time.

Though we did end as friends,

Given the chance we could love again.

She'll always love you forever,

It's not hard to believe.

I want you and I need you so I’m...

Sending you forget me nots,

To help me to remember.

Baby please forget me not,

I want you to remember.’

Patrice Rushen, ‘Forget Me Nots’ (P Rushen, T McFaddin, F Washington)

No. 480