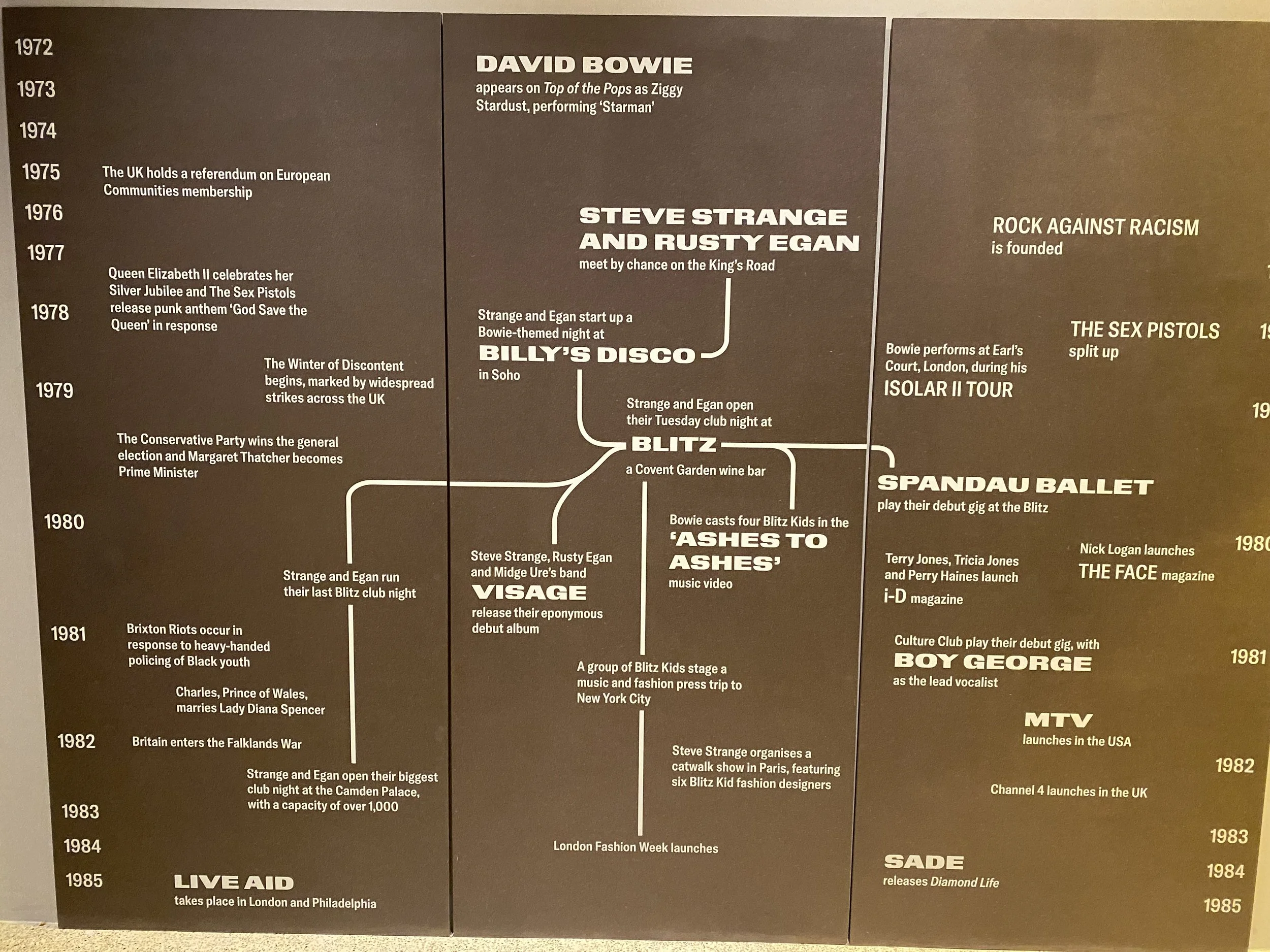

Blitz: The Art of Cultural Commentary

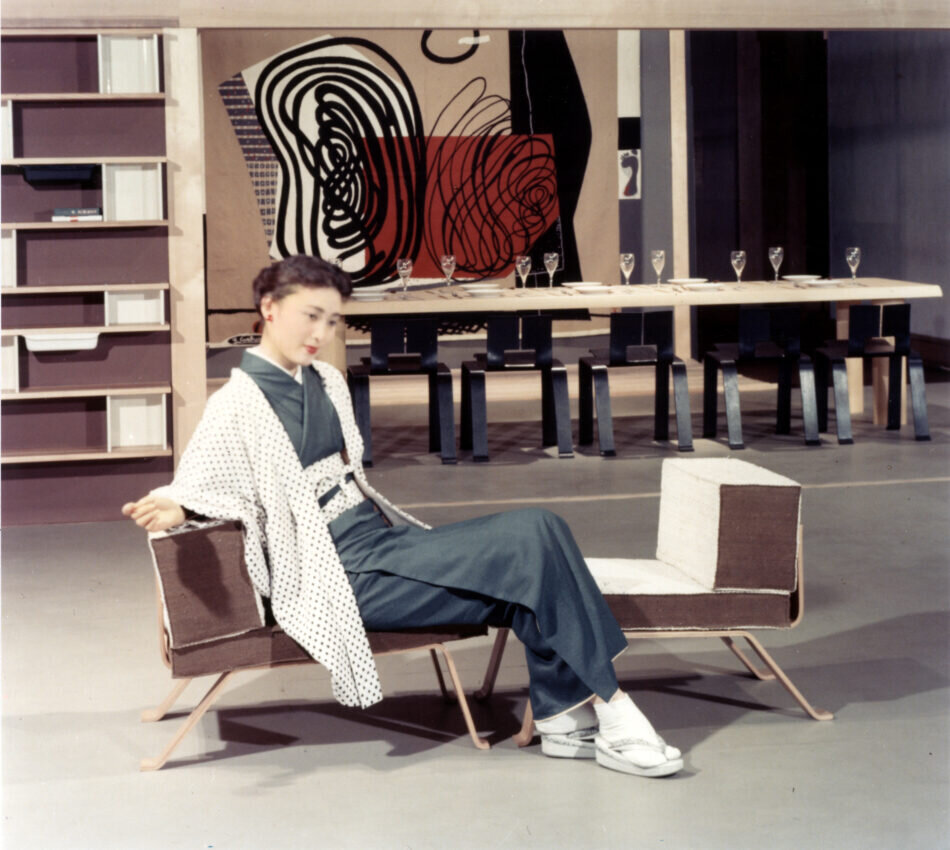

Photo Sheila Rock

‘From half-spoken shadows emerges a canvas. A kiss of light breaks to reveal a moment when all mirrors are redundant. Listen to the portrait of the dance of perfection. The Spandau Ballet.’

Excerpt from poem introducing Spandau Ballet on-stage, Robert Elms

I recently visited a splendid exhibition mapping the story of London’s Blitz club. (The Design Museum, London until 29 March 2026)

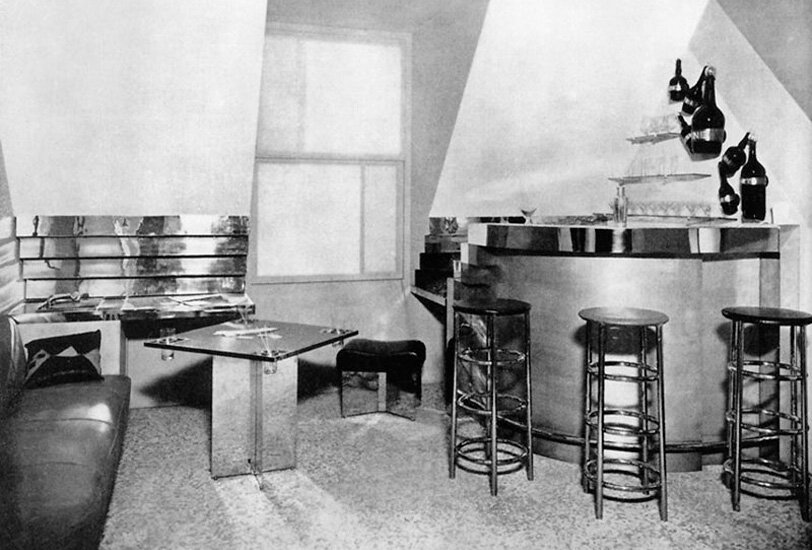

For eighteen months between 1979 and ‘80, this intimate Tuesday night event, held in a World War 2-themed wine bar on Great Queen Street, Covent Garden, was the vortex of a thriving creative community that embraced fashion and music, film, art and design. It was the spiritual birthplace of the New Romantic movement.

'One man on a lonely platform,

One case sitting by his side.

Two eyes staring cold and silent,

Shows fear as he turns to hide.

Aaah, we fade to grey (fade to grey)

Feel the rain like an English summer,

Hear the notes from a distant song.

Stepping out from a back shop poster,

Wishing life wouldn't be so long.

Aaah, we fade to grey (fade to grey).’

Visage, 'Fade to Grey’ (M Ure / C J Payne / W Currie)

Spandau Ballet, 1980 - Graham Smith

Publicised by word of mouth, the Blitz was co-hosted by Steve Strange and Rusty Egan - Strange enforcing a strict dress code at the door, Egan mixing art rock and electro-disco on the dance floor.

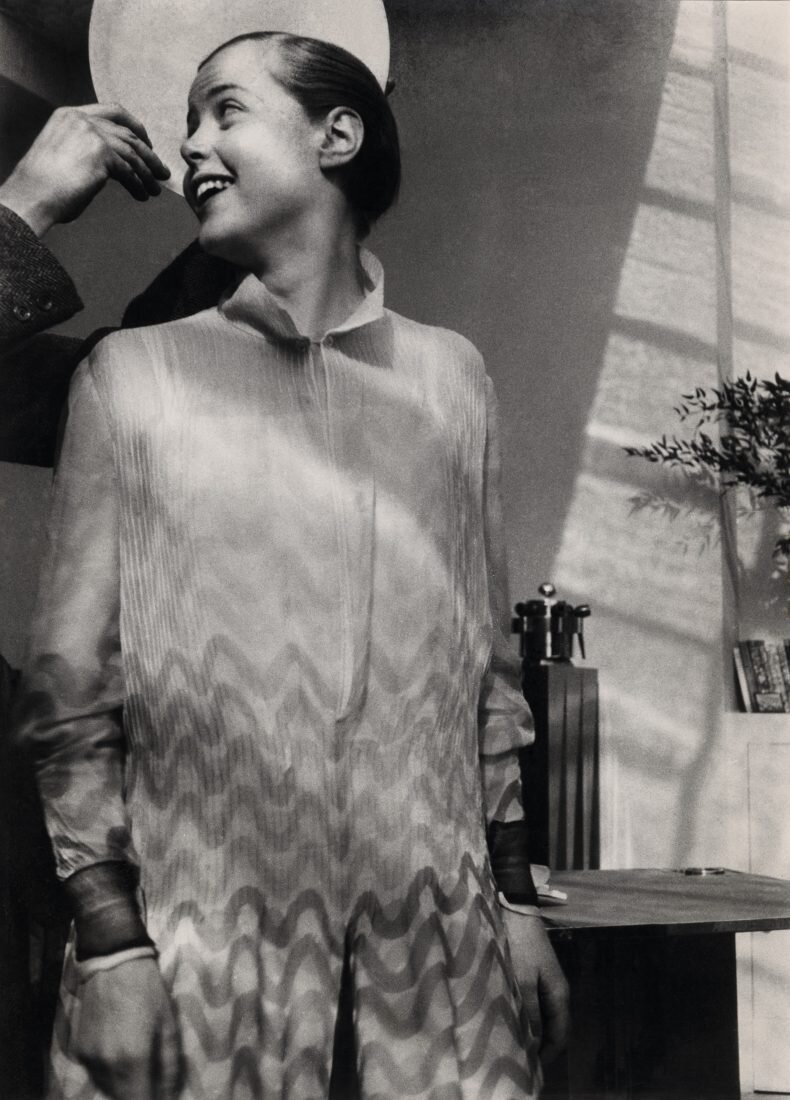

Since the Blitz was located between the Central and St Martin's Schools of Art, it attracted an inventive, style-conscious crowd. Combining vintage finds from second-hand charity stores, with pieces from theatrical costumiers and their own flamboyant designs, the Blitz Kids displayed bags of sartorial individualism and ingenuity. They embraced frills, ruffles and high-waisted trousers; androgynous make-up, elaborate hairdos and ostentatious hats. Their eclectic, fantastical outfits looked both backwards to the past and forwards to the future, evoking Weimar nightlife and the Golden Age of Hollywood; pirates, Pierrots, Bohemians and dandies.

‘[Fashion] is irrelevant – style is all important.’

Robert Elms

‘I can’t stand people who wear pound notes – money is no substitute for confidence.’

Christos Tolera

‘I hate the High Street and suppression of individuality.’

Christopher Sullivan

Boy George - Andy Rosen

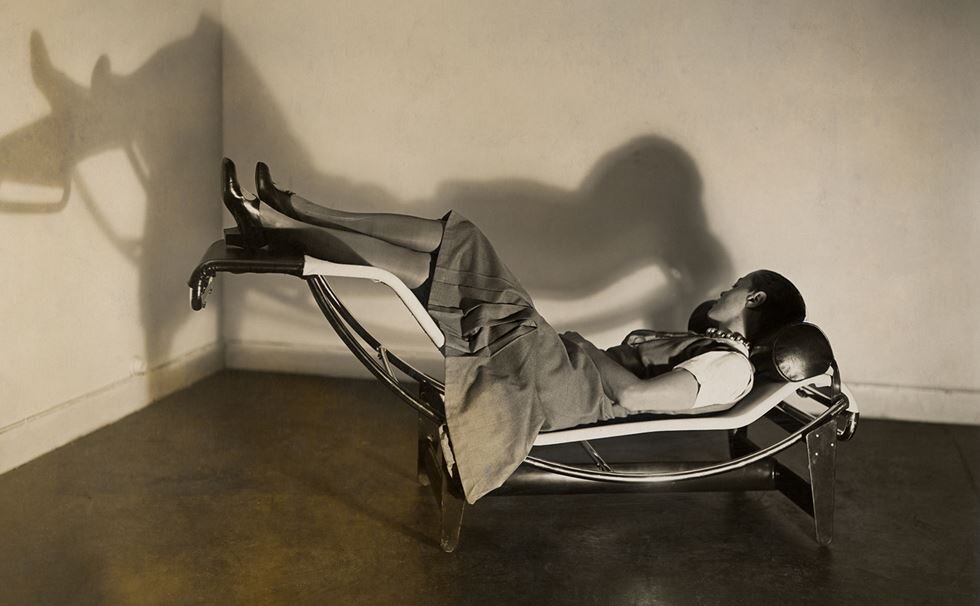

The show plots how the Blitz scene was born out of the economic and political turmoil of late 1970s Britain. Drawn from working class council estates and lower middle-class suburbs, the regulars took advantage of cheap rents and squats in central London; free university tuition and late-night buses. Kicking against drab consumerism and conventional youth culture, they were inspired by the restless creativity of David Bowie; by the experimentation of European avant-garde cinema and the sedition of punk; by the glamour of the soul scene and the transgression of drag acts and cabaret.

‘I feel the gaze against my skin,

I know this feeling is a lie.

There's a guilt within my mind,

I know this feeling is a lie.

I don't need this pressure on.

I don't need this pressure on.’

Spandau Ballet, 'Chant No. 1 (I Don't Need This Pressure On)’ (G Kemp)

The Blitz launched the careers of many musicians, including Spandau Ballet, Visage and Boy George (who was employed there as a cloakroom attendant). Influenced by Kraftwerk’s electronic sound, working with affordable synthesizers, innovative drum machines and reel-to-reel tape recorders, they created a futuristic brand of British synthpop. And while the music played, the clubbers - serious expressions on their faces, elbows pumping at their sides - engaged in their own jerky, metronomic dance. Like marionettes vogueing.

Marilyn 1982 - Robert Rosen

The Blitz catalysed new media vehicles, such as i-D magazine, and spawned a long list of designers, artists, filmmakers and writers - from couture milliner Stephen Jones and costume designer Michele Clapton, to DJ and fashion writer Princess Julia and broadcaster Robert Elms.

‘I’d find people at The Blitz who were possible only in my imagination. But they were real.’

Stephen Jones

I was particularly impressed by the curation of this exhibition (by Danielle Thom) – the way it isolated source influences and trends; critical figures, disciplines and dimensions; far-reaching impacts and effects. This kind of granular cultural commentary, with its neat charts and flow diagrams, can sometimes seem too well ordered. In reality, history is inevitably a little more messy. But the approach really helps understanding. It’s one from which all Strategists could learn.

Chronology - Photo Jim Carroll

In mid-1980, David Bowie visited the Blitz and invited Strange and three other regulars to appear in the video for his single ‘Ashes to Ashes.’ This elegant circularity helped propel the New Romantic movement into the mainstream.

I was too young to go the club (not that I’d have been let in), but old enough to comprehend its consequences. As with many such movements, in time New Romanticism became somewhat commercial and overblown; elitist, pretentious and absurd. But in its pomp, the Blitz clearly had something special: boundless creative energy and ideas; relentless optimism and youthful positivity. And it provided precious glamour to dispel the gloom.

'Soldier is turning,

See him through white light.

Running from strangers,

See you in the valley.

War upon war,

Heat upon heat.

To cut a long story short,

I lost my mind.

Sitting on a park bench,

Years away from fighting.

To cut a long story short,

I lost my mind.

Standing in the dark,

Oh, I was waiting for man to come.

I am beautiful and clean,

And so very very young.

To be standing in the street,

To be taken by someone.’

Spandau Ballet, 'To Cut a Long Story Short’ (G Kemp)

No. 541