‘The Best for the Most for the Least’: The Eames Office and the Democratic Impulse

'Eventually everything connects – people, ideas, objects…the quality of the connections is the key to quality per se.’

Charles Eames

I recently watched a fascinating documentary about the creative studio run by American designers Ray and Charles Eames (‘Eames: The Architect and the Painter’).

Charles Eames was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1907, studied architecture in Saint Louis and Michigan, and became a practicing architect. In 1940 with friend Eero Saarinen he entered a MOMA competition for 'Organic Design in Home Furnishings'. They were interested in the properties of plywood – how, with the application of heat and pressure, you could fashion the material in different directions and into smooth curves. They set out to design a chair that would mould to the body, that wouldn’t need costly upholstery and could be mass-produced.

Although they won the competition, they didn’t achieve their objectives. The glues were inferior, the chair split and they had to employ upholstery to cover the cracks. The project was shelved.

In 1941 Charles married the Sacramento-born painter Ray Kaiser. They moved to Los Angeles and started working together. Charles brought an architect’s logic and vision; Ray brought an artist’s confidence with colour and juxtaposition. They shared a youthful playfulness, curiosity and invention.

The Eameses’ first success came when they designed a new splint to help the war effort. The conventional metal models in service at the time vibrated, caused pain and aggravated wounds. Ray and Charles created a plywood splint that curved to reflect the shape of a human leg and had holes to remove tension.

‘The people we wanted to serve were various, and to begin with we studied the shape and posture of many types, averages and extremes.’

After the war, with the lessons learned from the splints, the Eameses revisited the plywood chair. Following an extensive period of testing, trial and error, the Eames Lounge Chair Wood (LCW) was born. It was elegant, light and comfortable, it needed no upholstery and it lent itself to industrial production - everything Charles had originally envisaged back in Michigan.

'Choose your corner, pick away at it carefully, intensely and to the best of your ability, and that way you might change the world.’

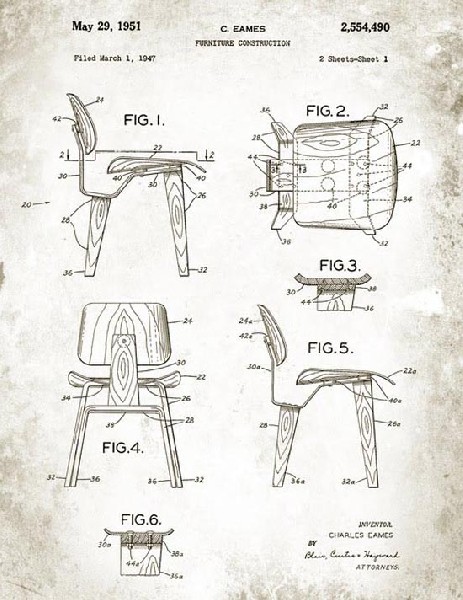

Patent Drawing for LCW chair 1947

In 1946, along with a family of plywood chairs, tables and folding screens, the Eames LCW was manufactured and sold by the Herman Miller Company. The range was an immediate success, resonating with a new educated suburban middle class that, after the privations of war, was looking for a fresh, accessible modern aesthetic.

'We don’t do ‘art’ – we solve problems. How do we get from where we are to where we want to be?'

The Eameses worked from a studio at 901 Washington Boulevard, Venice Beach. They designed the space to be flexible and informal. It could repeatedly shift shape to accommodate models, graphics, photography, filming and screening. And they hired young, open-minded, lateral thinking designers to work there.

‘Many of us understood very well that we were very poorly suited for employment in certain kinds of jobs. We were very suited to be there.’

Jeannine Oppewall, Designer

The Eames Office encouraged a vibrant creative culture. It avoided structure, routine and meetings. It was a living workshop of stimulus, ideas and experiments - and it organised field trips to the circus to provide inspiration and food for thought.

‘Take your pleasure seriously.’

The Eameses believed fundamentally in ‘learning by doing.’ They would build prototypes, test, adapt, reject and rethink. This exploratory process gave them a deeper, more intimate comprehension of the problem and took them closer to solving it.

‘Never delegate understanding.’

The working method was also rooted in rigorous study of end users – their physical form, their movement, habits and predispositions.

'The role of the architect, or the designer, is that of a very good, thoughtful host, all of whose energy goes into trying to anticipate the needs of his guests.’

The Eames Office continued to design furniture for the Herman Miller Company. It pioneered the use in furniture of technologies such as fiberglass, plastic resin and wire mesh. Its output included numerous classics: the chrome-based DSR (1948), the Eames Lounge Chair (1956), the Eames Aluminum Group (1958).

Charles and Ray Eames with the 1956 Lounge Chair

At the same time the Office took briefs from all manner of sectors. It was unconstrained by formal category definitions, technical expertise or experience. It worked on architecture projects. The Eames House at Pacific Palisades is regarded as a landmark of 20th century design. It curated exhibitions. It was commissioned by the Government to create a film representing the spirit of the United States to communist Russia; and by IBM to communicate the human value of the computer. Its short corporate videos were consistently charming and inventive. They took delight in explaining the complex in simple terms. Through the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s the Office’s Clients extended to include American titans like Westinghouse, Boeing, Polaroid and Alcoa. And yet Charles Eames always dealt directly with the CEOs, often without a written contract.

‘If you sell your expertise you have a limited repertoire. If you sell your ignorance it’s an unlimited repertoire. He [Charles] was selling his ignorance and his desire to learn about a subject. And the journey of him not knowing to knowing was his work.’

Richard Saul Wurman, TED Founder

Today’s marketing and communication industry is rightly seeking to break away from an excess of process, mediation and convention. We’re striving to re-orientate our working cultures around ‘making, not managing’. So there’s clearly a great deal we could learn from the Eames Office, the very paradigm of a contemporary creative studio.

1. Create an inspiring environment

2. Populate it with misfits and mavericks.

3. Seek to solve problems rather than to create art.

4. Take briefs from the top.

5. Never delegate understanding: focus relentlessly on the end user.

6. Learn by doing: prototype and model, test and learn.

7. Sell the boundless curiosity of your mind, not the narrow confines of your expertise.

8. Take your pleasure seriously: have fun!

I was particularly struck by the philosophy at the heart of the Eames Office: ‘We want to make the best for the most for the least.’

We may recognise in this simple democratic ideal the kind of admirable ambition articulated over the years by brands like Harrods, Wal-Mart, IKEA, and Google.

‘Omnia, omnibus, ubique.’ (‘Everything for everyone everywhere.’)

Harrods Motto

‘To give ordinary folk the chance to buy the same things as rich people.’

Wal-Mart Mission

'At IKEA our vision is to create a better everyday life for the many people.’

'To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.'

Google Mission

As Andy Warhol memorably observed, there is something very compelling about a truly democratic brand.

'You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.’

Working in the communication industry I found that it was always easier to develop interesting creative work for small, niche, prestige products and services. You are dealing with brands that are already inherently desirable, and with consumers that are already actively engaged. It is generally more challenging, and therefore more rewarding, to make work for big brands in ordinary, everyday sectors; to create content that has mass appeal, that talks to the mainstream, that impacts culture. And, what’s more, you may be performing a social good.

Charles Eames died in 1978 and the Eames Office was closed shortly after. Ray Eames passed away in 1988, ten years to the day after Charles. They are widely regarded as among America’s most important designers. They gave modernism a playful soul and a democratic intent. And the Eames LCW was selected by Time magazine as the greatest design of the twentieth century.

No. 208