Does Your Business Have Nightingale Floors? Learning to Recognise the Early Warning Signs of Danger

Nijo Castle gates

As a dignitary visiting the Shogun at his Nijo-jo Castle in Kyoto, you would pass through the magnificent Karamon Gate, with its Chinese-style gables and exquisite carvings of cranes, lions, pines and plum blossoms. Mindful of the Shogun’s power, you would perhaps hesitate as you entered the Ninomaru-goten Palace: 33 rooms and 800 tatami mats elegantly arranged within six connected buildings in a diagonal line. In the first and largest room, you would be greeted by fierce tigers painted on the bright golden walls. You would be ushered through more gold halls, these decorated with peacocks to signal the Shogun’s wealth, and pine trees to mark his everlasting prosperity. Your sense of awe and anticipation would gradually escalate as you were escorted quietly from one imposing chamber to the next. The Shogun awaits.

Kuroshoin (Inner Audience Chamber) Nijō Castle

On your route through the Palace you would marvel at the floorboards that sing like nightingales as you walk down the corridor. An attendant might explain that the sound of the nightingale floors is produced by clamps moving against nails driven into the wooden supporting beams. Are the floors designed merely to delight and impress, you wonder? Or are they an early warning system, announcing the presence of intruders?

As I paced along the corridor of the Ninomaru-goten Palace accompanied by a chorus of birdsong, my mind turned to early warning systems in business.

‘It’s a small project. We don’t want to distract you.’

If you work in an Agency and you hear these words, alarm bells should be ringing. What is being characterised as a modest and marginal initiative, may well be a door through which your competitors will come streaming in. It’s an early warning that your Clients find you boring, predictable, slow or expensive - perhaps all of these things. They’re keen to try out new talent, to find fresh ideas, to see how a different relationship feels.

‘The boss is very interested in this research project and has decided to attend the debrief next week.’

It is encouraging that your most senior Client is curious about a humble research debrief. But other motives could be at play. What if the Marketing team know which way the findings are heading and have invited their boss to witness your trial and execution? Maybe you’re being set up for a fall.

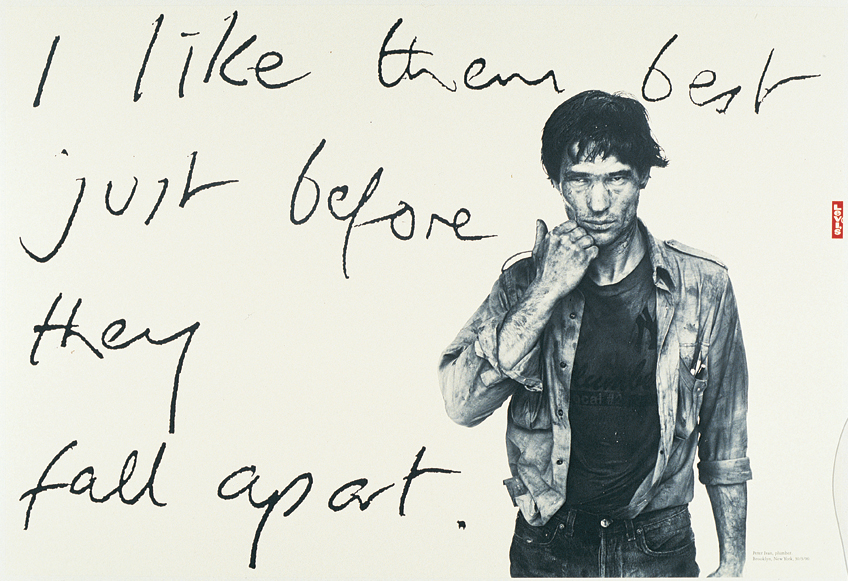

‘The work’s good, but is it great? Can we push it harder?’

Any Agency worth its salt should have an inner voice encouraging it to take ideas further and faster. In the natural course of events, it is the Clients’ role to rein the Agency back, to sound a note of realism and practicality. So when these challenging sentiments are expressed by your Clients, you should be concerned. The natural order has been overturned and it doesn’t bode well.

‘I think we need to design a new marketing model, something that reinvents the way our brand engages with consumers.’

Of course, all businesses need a new marketing model for the modern era. But you may find that this pronouncement positions you as the old marketing model - and therefore past your sell-by date.

‘As I’m new in this role I’d like the Agency to take me through the brand strategy, campaign thinking and performance data from the bottom up.’

The most obvious early warning sign for any Agency is the appointment of a new senior Client. But sometimes even when we know to be on our guard, we respond in completely the wrong way.

Many times in my Agency career we reassured our new Marketing Director with a presentation that detailed how well we knew the brand, how robust and effective the campaign was. It was only after a number of unfortunate encounters that I realised that new Marketing Directors interpret experience as orthodoxy, longevity as conservatism, confidence as complacency. They’re not looking to keep a gentle hand on the tiller. They’re keen to shake things up, to make their mark.

Uguisubari corridor (Nightingale Floor) Nijō Castle

All businesses need nightingale floors - a sensitivity to the subtle signs of impending crisis, an appreciation of the incidental events and innocuous remarks that in fact prefigure danger. If you’re lucky, your nightingale floors will alert you just in time to avert disaster.

And so finally you arrive in the Ohiroma or Grand Hall for your audience. The Shogun sits on a raised dais, facing south, attended by his court. You quiver a little. He doesn’t like to hear bad news.

Three hundred years or so later one would anticipate a meeting with John Bartle and Nigel Bogle with a similar sense of apprehension. They too commanded admiration and anxiety in equal measure. They too had an office on a raised step. But you knew as you approached them with your request to intervene on the account that was in crisis, that it was already too late. You should have acted sooner.

'I know the highest and the best.

I accord them all due respect.

But the brightest jewel inside of me

Glows with pleasure at my own stupidity.

This is a song from under the floorboards.

This is a song from where the wall is cracked.'

Magazine, 'A Song From Under the Floorboards' (Barry Adamson / Howard Devoto / John E Doyle / John Mc Geogh / David Tomlinson)

No. 204